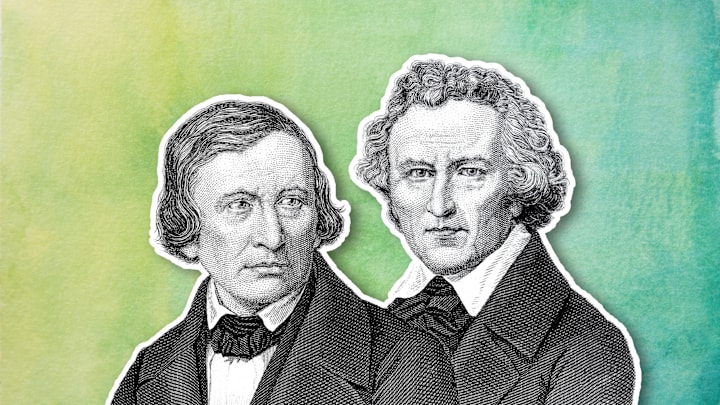

You’re probably familiar with Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, Snow White, Rapunzel, and countless other fairy tale characters, but many people are unfamiliar with the origins of the popular versions of these stories. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, more commonly referred to as simply the “Brothers Grimm,” were two German-born brothers who lived and worked in the 19th century as authors and collectors of folklore. They’re credited with popularizing more than 200 of our most-loved fairy tales with their most famous work, Children's and Household Tales—more commonly known as simply Grimms' Fairy Tales. Here’s what you need to know.

1. Like a lot of the characters in their stories, the brothers Grimm had a bit of a “rags-to-riches” story.

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were born in 1785 and 1786, respectively, in what is now present-day Germany, to Philipp and Dorothea Grimm. Although the brothers were two of nine children (only six of whom survived to be adults), they spent the first few years of their lives in relative comfort—residing in a large home in the country and receiving at-home schooling with private tutors.

But as Jack Zipes writes in Brothers Grimm: From Enchanted Forests to the Modern World, everything changed when their father died in 1796 and the family was plunged into poverty. The two young Grimm boys were forced to grow up quickly, and their new, lower social status was cemented as soon as they began their public schooling and found a large class divide between them and their wealthier peers.

This disparity only grew when the boys applied for university: While students of higher social standing were automatically enrolled, the Grimms were disqualified from admission because of their low status and forced to request a special dispensation to attend. But the brothers took this “outsider” status in stride and dedicated themselves to their studies with extra zeal; they remained hard workers for the rest of their lives, and would eventually become household names.

2. The Brothers Grimm studied law.

Like their father, who had been a civil servant, Jacob and Wilhelm went to university to study law with the intent of becoming civil servants themselves. Eventually, however, the brothers “came to believe that language rather than law was the ultimate bond that united the German people,” Zipes wrote in the introduction to The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm, “and were thus drawn to the study of old German literature.” They threw themselves into collecting texts with zeal and set a new goal: to become librarians and scholars of the stories they loved so much.

3. Over 50 of the brothers’ stories were almost lost to history.

According to Zipes, the Grimms began “systematically gathering” folktales in 1807—but it wasn’t for their own project. The previous year, writer Clemens Brentano had asked for the brothers’ help while readying his own collection of folktales for publication. “The Grimms responded by collecting oral tales with the help of friends and acquaintances … and by selecting tales and the from old books and documents from their own library,” Zipes writes. From 1807 to 1810, they collected, transcribed, and organized a total of 49 stories to send to Brentano.

At some point, Brentano either forgot or abandoned his copies in a church in Alsace, where they would not be unearthed until 1920. These stories became known as the Ölenberg manuscript, and are believed to be the oldest surviving records of the Grimms’ work.

Luckily, the brothers made copies of what they had done before sending it off to Brentano (Zipes writes that they were concerned he “would take great poetic license and turn them into substantially different tales”), and were able to publish the first edition of Grimms’ Fairy Tales in 1812.

4. The brothers were two members of a group of political activists that would become known as the Göttingen Seven.

The brothers spent seven years employed at the University of Göttingen as professors and librarians before they were fired in 1837 for protesting against the new King Ernest Augustus of Hanover. In addition to annulling the country’s constitution to meet his personal whims, the king also demanded that civil servants—including professors—sign an oath of fealty to him. The brothers and five other men at the university who openly resisted were dismissed from their posts and became known as the “Göttingen Seven.” This brave stand succeeded in bringing public attention to the king’s tyranny, and the seven were soon very popular in Germany and the rest of Europe.

5. Although associated with many of the modern forms of the tales that we know today, the brothers didn’t come up with these stories themselves.

It’s difficult to trace the exact origin of any single folktale—most were passed down orally through generations, and, like a game of telephone, things were bound to be misheard or omitted. Most of the versions of fairy tales that we know today are a mishmash of different stories, though the general theme remains the same. Take Cinderella: According to National Geographic, versions of the tale can be found everywhere from ancient Egypt to the West Indies to ancient China, with details like the material of her slippers to the food that turns into her coach differing from culture to culture. (The Egyptian version has slippers made of red leather rather than glass, for example, while in the ancient Chinese version they’re made of gold.) The brothers merely polished them to make them more cohesive for the masses.

6. Their stories weren’t originally aimed at children …

What would become one of the most famous collections of children’s tales ever began as a study of German oral traditions. The Grimms believed that stories passed down from generation to generation were an important part of German culture. “The more they began gathering tales, the more they became totally devoted to uncovering the ‘natural poetry’ (Naturpoesie) of the German people, and all their research was geared toward exploring the epics, sagas, and tales that contained what they thought were essential truths about the German cultural heritage,” Zipes writes in The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm, the first English-language translation of the original version of the Grimms’ stories. “Underlying their work was a pronounced romantic urge to excavate and preserve German cultural contributions made by the common people before the stories became extinct."

They gathered as many stories as they could, and they didn’t sugarcoat them, either: Chi Luu writes at JSTOR Daily that the Grimm brothers found the polished moral tales peddled to the upper classes “to be more fakelore than folklore.” The Grimms themselves said that they sought to record the tales as they were told by the people—violence, dialect, slang, and all (though that would not turn out to be entirely true).

7. … And required a fair bit of editing to become more kid-friendly.

It’s understandable that parents would expect a book of stories called Children’s and Household Tales to be a family-friendly read, but the first edition of the brothers’ collection didn’t exactly hit that mark. There were complaints that the stories were too dark for children, and some of the more puritanical readers lamented the lack of overt Christian themes. So the brothers edited their tales, publishing more than a dozen editions: The unwed Rapunzel no longer became pregnant; Cinderella’s stepsisters did not cut off parts of their own feet while attempting to make the slipper fit; and Snow White’s murderous mother was changed into her stepmother.

8. The Brothers changed their stories to promote a stronger sense of German nationalism, which lead to the Nazis later using them to promote their own agenda.

The Grimms lived during the unstable time of the Napoleonic Wars, and wanted to bolster a sense of patriotism throughout the fractured German-speaking realm. According to Luu, they tweaked some of the tales so that they appeared to be more German than they actually were—for example, a story originally known as “The Little Brother and the Little Sister” was retitled with two German names: Hansel and Gretel. Perhaps unsurprisingly, over a century later, the Nazis began interpreting nationalism to mean “Aryanism,” and Hitler liked the Grimms’ collection so much that he decreed it be taught in every German school.