Dodos never had the best reputation. The extinct, flightless birds are often labeled as slow, awkward, and incompetent. But that may soon change, as scientists have discovered dodos were stronger and faster than previously assumed.

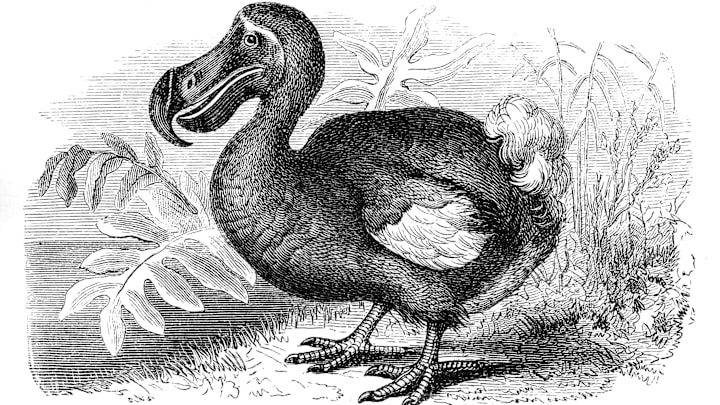

Misconceptions surround the dodo because people know so little about them. The classic image of the squat, bumbling bird we have today comes from descriptions from Dutch sailors and artists, as well as incomplete fossils. The species was driven to extinction by humans in the late 17th century. This was before collecting a “type specimen”—a single, preserved creature used as a reference for a new species—became a regular practice. Zoological nomenclature, the system of classifying and labeling animals, wasn’t established at the time either, causing many of the dodo’s characteristics to be misidentified.

To uncover more about the extinct species, researchers from the University of Southampton, the Natural History Museum in London, and the Oxford University Museum of Natural History reexamined several resources dating back to 1598, including historical literature and dodo specimens. They recently published their findings in Zoological Journal.

According to the Natural History Museum, the scientists determined that the bird was built differently from what we’re used to seeing. We typically imagine dodos as plump animals that easily died out due to their slow and docile nature. However, this recent study shows that they were leaner than most people think. The dodos’ bone structure also implies they were fast and active.

Dr. Neil Gostling, a palaeobiologist from the University of Southampton, explained in a press statement that “the dodo’s tendon which closed its toes was exceptionally powerful, analogous to climbing and running birds alive today.”

The research team confirmed the bird belonged to the dove and pigeon family. They also found that the dodo and its close (also extinct) relative the solitaire were the only members of their subfamily, and similar species discovered throughout the years were incorrectly categorized.

So how did the species get such an unfortunate rap? The iconic drawings of the bird from the 1600s likely didn’t show them under typical circumstances. The subjects of those sketches may have been overfed captives, or overstuffed specimens. When food was more scarce, the creature’s lean build was probably more apparent.

It may take a while to dispel the inaccuracies attached to the species. In the meantime, the birds are still benefiting us 350 years after their demise: because dodos played a major role in their ecosystem, the new research brings us closer to ecological recovery in their native home of Mauritius.

Read More About Extinction: