In the early 1980s, Jim Henson was riding high.

His Muppets could be seen on Sesame Street, which had already been a fixture of children’s television programming for more than a decade. Adults might recognize his characters from brief, early appearances on Saturday Night Live or The Muppet Show, an English production that had found a home on American television and spawned to that point a pair of movies, 1979’s The Muppet Movie and The Great Muppet Caper two years later.

But Henson’s sights were set even higher than that: Creating a show that was not just sold to international markets, but made for them, with the idea of finding common ground through his positive messages.

“The goal was to bring about world peace,” Karen Falk, archives director for The Jim Henson Company, tells Mental Floss. “Jim had an overall interest in making international connections and having an impact internationally.”

World Peace in the Cold War

The show he saw as being able to achieve that goal was Fraggle Rock, which premiered on HBO—a nascent, pay-television network that only a year earlier had committed to 24-hour programming—on January 10, 1983. Six years later, almost to the day, the show premiered on television in the Soviet Union, in what turned out to be the waning days of the Cold War.

“We like to say that Fraggle Rock maybe had something to do with that,” Falk says.

Henson’s fascination with Russia went back to the start of his professional career. His college years and early career coincided with the early days of television, which provided puppetry opportunities for him. To learn more he read My Profession, a memoir by Sergey Obraztsov, a Russian puppeteer heralded worldwide as one of the greatest. In 1958, Henson took a trip to Europe to learn more. “In the United States, puppetry was seen as a children’s art form,” Falk says. “In Europe, it was much more venerated as an art form and thought of as high art.”

There was a group of puppet artists in Europe called UNIMA (Union Internationale de la Marionnette), which had formed in the 1920s but began meeting again in 1957. Henson joined up and, in fact, started the group’s U.S. chapter. The group would meet throughout Europe, including in countries that had become Soviet satellite nations. “He had this interest in connecting with puppeteers and sharing culture on both sides of the iron curtain,” Falk says.

Henson’s Muppets, whose energy was described by Henson collaborator Jerry Juhl as “affectionate anarchy,” made a variety of television appearances in the 1960s, from the The Ed Sullivan Show (including some familiar characters) to coffee commercials. When a groundbreaking educational show called Sesame Street was being developed in the late 1960s, Henson’s Muppets were regarded as an essential inclusion.

The Kids are Alright

But Henson didn’t want to be typecast as just a children’s entertainer. American networks were disinterested in his prime-time pilots of his Muppets, but Lord Lew Grade, a British impresario whose company ITV developed British TV shows like The Saint and The Prisoner (as well as the puppet kids’ show Thunderbirds) was interested. The Muppet Show was produced for British television and sold into syndication in the United States, where it proved to be a hit. (The producer played by Orson Welles in The Muppet Movie, who gives the Muppets their big break with “a standard rich and famous contract,” is named Lew Lord in tribute.)

Henson was ready to make his next project intentionally international. Puppet shows could easily be dubbed into foreign languages—and already were. Sesame Street had gone into co-production in other countries; an original live-action “Street” was set up in other countries, and inserts involving the Muppets were dubbed for foreign audiences.

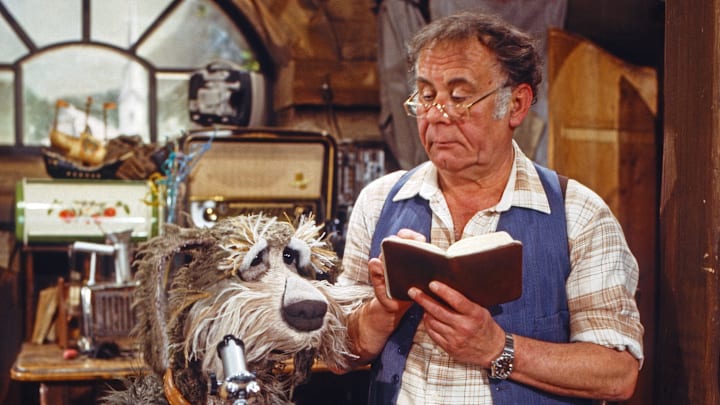

The main characters of Fraggle Rock were the eponymous Fraggles, puppets who lived underground and interacted with other puppets, namely the Doozers and Gorgs, as well as humans, whom they called strange creatures from “outer space.” The human in the American version was Doc, an itinerant inventor. In the British version, he was a lighthouse keeper. In France, he was a chef. The show was seen in nearly 100 countries—including, eventually, the Soviet Union. Thanks, in part, to The Dark Crystal.

The 1982 fantasy movie was a Henson creation, yet it was a departure from the Muppets he had become known for. The initial reaction to it was mixed (today it’s a cult classic and an important part of the Jim Henson canon), but it was a full-throated hit in Russia, where it was shown—initially, to little fanfare—at the Moscow Film Festival.

“Screenings were sold out,” Falk says. “There were lines around the block. They had to put extra screenings out. It got Jim Henson’s attention.”

To Russia With Jim

Cheryl Henson, the second of Jim Henson’s five children, had studied in Russia while at Yale University, and she and her father attended a UNIMA conference in what was then East Germany in 1984, developing plans for a documentary, Jim Henson’s World of Puppetry, which of course included an interview with the aged but still influential Obraztsov.

The Cold War was also thawing at that point. In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev became the leader of the Soviet Union. He was a marked change from the aged and infirmed men who had led the nation before him. He was also a reformer, promising perestroika, or restructuring, and glasnost, more openness.

And that extended to television. Fred Rogers recorded an episode of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood with the puppets of Good Night, Little Ones, a longtime Russian children’s program. The pig and rabbit from Good Night, Little Ones also met Kermit the Frog and Miss Piggy in the 1988 Marlo Thomas special Free To Be … A Family.

“The whole landscape of television in Russia was transforming at record speed at the time,” Natasha Lance Rogoff, a documentarian who lived in the Soviet Union during that era, tells Mental Floss. “You also had the blossoming of advertising.”

An episode of Fraggle Rock was shown on Soviet television on January 8, 1989. By then, the series had run its course in America (it aired for five seasons, from 1983 to 1987), and Henson had moved on to other projects. But the viewer numbers in the Soviet Union for that single episode were described by Henson’s company as “unprecedented.” Plans were made to start airing Fraggle Rock in its entirety, making it the first American series to air in the Soviet Union.

The first season was dubbed—there was no co-production, just a narrator who described the action in Russian—and began airing in the fall of 1989. It would turn out to be one of the last great achievements in Henson's lifetime; he died on May 16, 1990.

Not long after Fraggle Rock began airing in the USSR, the Berlin Wall fell. Soon, the Iron Curtain had crumbled altogether, which led to another opportunity for Henson in the Soviet Union: Their own co-production of Sesame Street. Rogoff was approached about working the project and—reluctantly, at least initially—accepted. The Russian Sesame Street, called Ulitsa Sezam, premiered in 1996.

“Jim Henson’s brilliance made it possible for us to bring Sesame Street to Russia at a critical time when there was very little children’s television of high quality,” says Rogoff, who recently wrote a book about the experience, Muppets in Moscow: The Unexpected Crazy True Story of Making Sesame Street in Russia. “The popularity of the show in Russia is a testament to his genius, and the Muppet sensibility of humor, kindness, and humanity is Jim Henson’s legacy.”