On December 16, 1931, Nell Donnelly found out her life was worth exactly $75,000.

Donnelly, a prominent Kansas City fashion designer whose clothing could be found in closets all over the country—and whose financial success was well-known—had been bound and driven to a dilapidated house, where she and her chauffeur, George Blair, were held against their will. She was given a dire warning: Either her family would deliver $75,000—worth roughly $1.3 million today—or the kidnappers would kill Blair. Donnelly would be spared, they said. Instead of killing her, they’d merely blind her.

Donnelly and Blair were undoubtedly terrified. But the two would soon discover that help was coming from the very same criminal underworld that had put them in their predicament. And some 80 years later, the world would learn that Donnelly harbored a secret—one that would heavily influence how one of the most sensational kidnappings of the 1930s would unfold.

Loose Threads

The Great Depression, which began in 1929 and lasted for about 10 years, was a time of extreme economic desperation: At the peak of the downturn, the unemployment rate in the United States was more than 20 percent. Circumstances became so dire that some citizens were propelled to turn to crime—kidnappings in particular became the ultimate get-rich-quick scheme, and thousands were carried out in what became a virtual epidemic. The abduction of famed aviator Charles Lindbergh’s infant son in March 1932 was the highest-profile example, but anyone of means could be a target. And Nell Donnelly certainly fit the criteria.

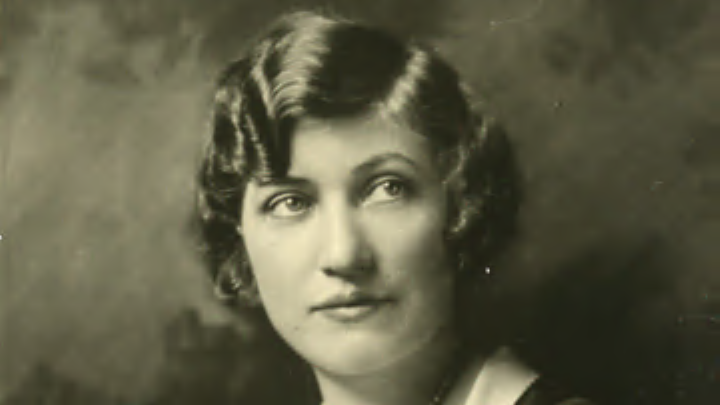

Born Ellen Quinlan on March 6, 1889, Donnelly first drew attention in 1916 for her ruffled dress designs, which became popular as a contrast to the plain cotton dresses common in pre-World War I America. Stylish attire was usually more expensive, but Donnelly’s Nelly Don label offered flair for a modest premium—a Nelly Don dress might cost $1 compared to 69 cents for a comparatively drab outfit. The styles and textiles were inspired by her trips to Paris and Vienna, but she kept them pragmatic: Most Nelly Dons, as they were called, had pockets. Donnelly also recognized a need for attractive clothing for customers of all sizes, fashioning dresses not just for trim consumers but for anyone who wanted them.

Sales soared; her Donnelly Garment Company would eventually grow into a $3.5 million business employing over 1000 people, most of them women. But Donnelly’s business acumen went beyond knowing what her buyers wanted. Despite the economic strain of the Great Depression, she treated her employees equitably, offering pension plans, health insurance, and paid tuition for workers looking to further their education. She also established a scholarship fund for the children of her employees.

On the surface, her domestic life seemed as orderly as her business affairs. Donnelly was married to husband and business partner Paul Donnelly, with the two permanently relocating to Kansas City after Nell graduated from Lindenwood College in St. Charles, Missouri. The couple and their adopted son, David, settled into a life of social prominence.

Unfortunately, Donnelly’s social stature and success made her a target. On the evening of December 16, 1931, she exited her office and climbed into a car driven by her chauffeur, George Blair. As they arrived home, the entrance to the driveway was suddenly blocked by another vehicle. A man appeared in front of the car holding a gun. He quickly entered Donnelly’s car and subdued Blair by forcing him to the floor. In the back seat, Donnelly struggled with two men attempting to put a sack over her head. Realizing she was being kidnapped, she began to kick and scream.

Criminal Intent

Donnelly and Blair were soon ushered out of their own car and into another vehicle. Donnelly was far from a docile victim—she managed to kick the car door open at one point. After roughly an hour or so of driving, they arrived at a modest cottage doubling as a safe house, one in which her kidnappers would plot their next move.

“We took you because we want money,” Donnelly later claimed they told her. “We are not going to hurt you if you will do as we tell you. We will treat you all right, but we want $75,000.” Donnelly was ordered to write her own ransom note, in which she communicated their demand for money or else they’d kill Blair and blind her. Grievous injury was also promised if anyone contacted the police. Donnelly told them she didn’t want to address the note to her husband, Paul, who had been ill for weeks and wasn’t in the shape to receive such news.

Eventually, she agreed to write one to Paul and one to James E. Taylor, the family’s personal attorney. Then Blair and Donnelly were taken to a room where he was bound on a cot and blindfolded with a towel. Donnelly was allowed to lay on a bed but was not blindfolded, as she had promised not to look at any of the abductors. Their captors provided milk and crackers.

The next morning’s mail delivered the note to Taylor. The lawyer had initially dismissed a call notifying him that Donnelly’s car had been abandoned at a Kansas City theater, but the letter was a clear signal that someone had taken her. Now aware this was no joke, Taylor raced over to consult with Donnelly’s husband, Paul, who was shocked by the news. While he had taken note of his wife’s absence the evening before, he assumed she had gone out with friends and would be home after he fell asleep. “What is done now means the difference between life and death,” Paul told reporters. “We must find a way to get the $75,000 into the hands of those men who are holding my wife. If more is needed we’ll get it. But let’s have her released at once.”

Paul and Taylor decided to enlist Taylor’s law partner James Reed, a former U.S. senator and onetime mayor of Kansas City from 1900 to 1903; he had even run for presidential office in 1924 and 1928. Not only that, Reed was a neighbor of the Donnellys and a family friend. But requesting Reed’s help had an unintended consequence: When Reed asked to be excused from court to come to the Donnellys’ aid, he inadvertently tipped off reporters to the kidnapping. Police quickly arrived on the scene, and the kidnappers’ preference for a private transaction was out the window.

Reed, feeling a sense of urgency, did two things: He made a public proclamation that the ransom would be paid providing no harm came to Donnelly and Blair, and he made a crucial phone call. In addition to all of his political connections, Reed also had a line to the criminal underworld. He called Johnny Lazia, a notorious Kansas City organized crime boss with strong ties to local government, and barked out a demand. Either Lazia could use his manpower to help search for Donnelly, or Reed would begin a campaign to shame Lazia publicly and go after his criminal enterprise with whatever legal means he had at his disposal.

It was a kind of blackmail, albeit for a noble cause. Lazia agreed. Quickly, Kansas City was overrun with hoods knocking on doors and colluding with one another to find out if anyone in their criminal circle had kidnapped Donnelly. They patrolled the city in cars, guns hanging from their hips, as though they had been deputized.

While Lazia’s patrol canvassed neighborhoods, Kansas City police were short on leads and opted to put pressure on Savannah Blair, the wife of driver and victim George Blair. Officers were reported to have physically assaulted Savannah in an attempt to extract information before she was arrested. When a neighbor tried to intervene, he, too, was attacked. It was a futile and cruel episode that demonstrated that Reed may have had the right idea about enlisting Lazia rather than to trust police to settle the matter.

Roughly 34 hours into the ordeal, some of Lazia’s underlings were able to discern that the kidnapping victims were being housed in a farm near Edwardsville, Kansas. The kidnappers were told in no uncertain terms that the crime had not been blessed by Lazia and was therefore a fool’s errand, and they’d never get away with it.

The men were convinced. Soon, Donnelly heard an unfamiliar voice. “These are out of town men,” the strange man said. “They made a mistake.” The blindfolded Donnelly and Blair were then guided into a waiting car, driven to the outskirts of Kansas City, and dropped off, where police acting on an anonymous phone call tip retrieved them unharmed at roughly 4:30 p.m. on December 18. But the story was far from over.

A Twist of Fate

Back home, Donnelly was able to make a positive identification of one of her kidnappers: Martin Depew, a steam shovel operator.

Curiously, Depew’s wife, Ethel, was a nurse who had been to the Donnelly residence a year prior to attend to Paul. It’s possible that’s when a plan to squeeze the family for money was hatched and that perhaps Paul was Depew’s initial target before they stumbled upon Nell. Depew was tracked down in South Africa and extradited to the U.S. in 1932, and later given a life sentence (though he would be released when he came up for parole in 1947). Walter Werner, one of his accomplices who also fled to South Africa, was given a life sentence as well, with his defense resting on the argument he believed the kidnapping had all been a harmless publicity stunt approved by a “banker and an attorney for Mrs. Donnelly’s husband.” Charles Mele, the third kidnapper, got a comparatively light 35-year sentence.

Donnelly’s recovery caused a media firestorm: Her accounts of being held hostage and threatened took up inches of newspaper space and raised her profile even more. The incident also seemed to strengthen her bond with George Blair, whom she promised a job for life.

Her relationship with Paul was a different story. In November 1932, about a year after the kidnapping, the Donnellys divorced; Nell purchased Paul’s stake in her company.

The next year, Nell remarried, exchanging vows with none other than the man who had been her savior—James Reed. Nell was 44 at the time; Reed, 72. Decades later, members of Nell’s family would disclose that Nell and Reed had a preexisting relationship, one that predated the kidnapping and resulted in a son, David. Nell and Paul had “adopted” David to raise as their own rather than risk a public scandal.

It was Reed’s affection for Nell that likely provoked him into taking the highly unusual step of turning to the criminal underworld for help after her abduction. He was searching not only for a family friend, but his son’s mother. Without that emotional investment and Lazia’s pressure, it’s unknown whether Kansas City police would have been successful in locating Donnelly and Blair, or if kidnappers would have delivered on their gruesome promises.

After the abduction, Donnelly’s success continued to grow. In 1935, Forbes described her as probably the most successful businesswoman in America. She remained married to Reed until his death in 1944; she lived until the age of 102.

Johnny Lazia didn’t quite share in their happy ending. Though he continued to amass power and influence in Kansas City, even using his jurisdictional ties to help staff local police with former criminals, he couldn’t avoid the violence that the underworld thrives on: He was gunned down in 1934. Although the killers were never captured, it seemed that the criminal circle that had once spared Nell Donnelly’s life was all too happy to take Lazia’s.