You might think of Neopets as nothing more than an Internet-based Tamagotchi—a ‘90s-era web page that allowed users to care for pixelated penguins and dragons. But what if we told you that it trained a generation of 13-year-olds to become skilled computer coders? Or that it broke new ground in social networking before MySpace, and even before Facebook was a gleam in Mark Zuckerberg’s metaverse? That these digital creatures taught an entire generation of kids to be computer-savvy and even got them well-versed in the stock market? And that part of its success was due to Scientology?

All of that is true. Neopets was the trojan horse of early websites, a sneaky and seemingly simplistic interactive pet simulation that wound up becoming something much, much bigger. It was like Tamagotchi meets Wall Street. But to understand how Neopets made such an impact, we need to first take a look back at the primitive wasteland that was the internet of 1999.

- Pet Project

- A Religious Experience

- Neopets as Edutainment

- Neoscams

- The Neopets Universe

- The Neopets Legacy

Pet Project

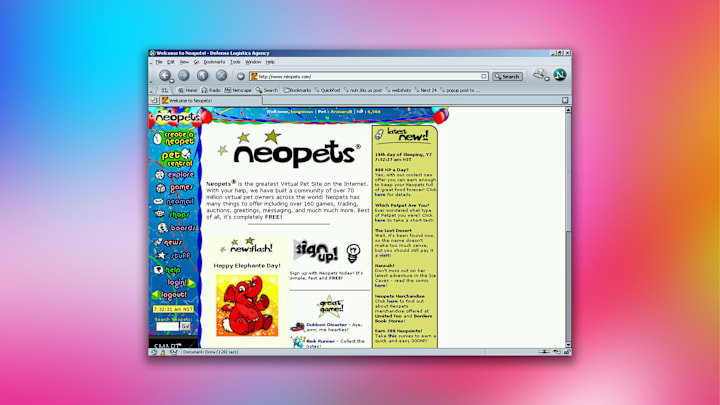

By the end of the 1990s, personal computers were in roughly 50 percent of households and people were getting accustomed to the idea of the internet as a valuable resource. Yahoo was the premiere search engine; Google was still in beta testing. Enterprising users were building their own websites on Geocities or pouring their hearts out on LiveJournal, probably while listening to “All Star” by Smash Mouth and wearing a Gap hoodie.

There were only about 8 million teenagers using the internet at the time, but despite that relatively low number, Adam Powell and Donna Williams thought they were being underserved by the internet’s paltry interactive offerings. Their focus was on building a platform for university students that might net them some income from banner ads.

Adam was a capable programmer who was designing ads for his father’s hot water bottle business. Donna had studied sculpture and graphic design. Adam took note of Pokémon, that trading card and video game sensation, and had an idea. Why not do something similar on the web? The result was Neopets, a virtual pet utopia where visitors could build different cyber pets, customizing their gender, color, and breed. Options ranged from your average housecat to mythical creatures like dragons.

Like Tamagotchi, the popular handheld game that had recently come out, users had to care for their digital dependents by feeding them and playing with them. Unlike Tamagotchi, Neopets wouldn’t drop dead from neglect. Plus, these hybrid animals—with names like Nimmo, JubJub, Korbat, and Grarrl—were colorful and well-rendered compared to the digital handheld pets. Adam and Donna hoped that people would keep returning to the Neopets site to care for their quirky animals and get exposed to some advertising while doing it.

But this wasn’t just an in-browser version of Tamagotchi. Adam and Donna built an infrastructure around the pets that made everything feel more real. Users were dubbed Neopians. The characters could take up residence in the Flash-animated world of Neopia, living in different areas that were divided up like amusement park locations with names like Mystery Island and Terror Mountain. The game even had its own newspaper, The Neopian Times, that had everything from cartoons to editorials about the Neopia economy.

Yes—an economy. There were no free rides in Neopia. If you owned a Neopet, you had to play games to earn credits, known as Neopoints. The games resembled staples like solitaire, Minesweeper, Tetris, and even Whac-a-Mole. Neopoints could be redeemed for food, pet costumes, toys, and tiny pet homes. You could even buy pets for your Neopets—called petpets—and pets for those pets (which were petpetpets).

Once they built up an impressive stash of digital currency, users could humble-brag about their virtual wealth with other users. They could also join guilds, which is what Neopets called sub-groups for fans of different television shows, movies, books, and music. Logging in didn’t mean you had to talk about your pets. You could also talk about Dawson’s Creek, or how much you loved Jar-Jar Binks in Star Wars: Episode One.

Neopets only offered nine pets when it launched in November 1999. The site took off quickly: Soon, more than 500 people a day were signing up. Then traffic started to double every week. Adam and Donna saw potential for Neopets to grow, but they were more content creators than businesspeople. They needed someone to take Neopets to the next level.

A Religious Experience

The early success of Neopets caught the attention of Doug Dohring, the founder of the Dohring Company, a market research firm. Dohring and his partners bought the site, freeing up Adam and Donna to focus on the creative side while Dohring concentrated on a business model.

Dohring happened to be a member of the Church of Scientology, the controversial religious organization. It undoubtedly had an influence on Neopets. Eventually, four of the six members of Neopets’ executive team were Scientologists. Dohring used a business model that Scientology calls Org Board, which splits key focus areas like communications, production, and public relations into different umbrellas. The finer details of Org Board are a closely-guarded secret, but Dohring made use of some of its practices, including asking potential employees which straight line on a page seemed “friendlier,” as Donna recounted in a 2014 Reddit AMA. Dohring even voiced a desire to post Scientology literature on the site—an idea that Adam and Donna, who are not members of the church, shut down. They didn’t want Neopets to be denominational.

There was another aspect to Neopets that caused some controversy. Neopets helped pioneer something called immersive advertising, a phrase they later trademarked. Instead of a banner ad, like Adam and Donna had pursued, players in the game would be subjected to in-world advertising. A Neopet might encounter a breakfast cereal character like the Trix rabbit, or places might be modeled after an advertising sponsor like Cartoon Network or McDonald’s. Gotta brush? They could grab some digital Crest toothpaste. If a pet was thirsty, their owner could buy a Capri Sun for it. And according to a Harvard Business School paper, during one campaign children commented things like “When I saw Capri Sun on the site I had my mom go buy some so I could drink it with my pet.” Pretty soon LEGO, Frito-Lay, and Disney were popping up on the site. It was an early example of internet product placement, and many users probably had no idea they were in the middle of an advertisement.

Consumer advocates like Ralph Nader argued that it was sneaky to market products to kids in the middle of a game without some kind of disclosure. But the people behind Neopets countered that no kid was forced into buying sponsored products or playing sponsored games.

Some parents were also displeased to learn that kids could earn—or lose—Neopoints by playing casino games like roulette or blackjack. In response, the site mandated players of those games had to be 13 or older.

Whatever the merits or ethics of advertising or child gambling, Neopets was quickly becoming about something much more than toothpaste. Something Adam and Donna hadn’t anticipated. It was turning into a learning experience.

Neopets as Edutainment

By 2005, Neopets was poised for another big breakthrough. It had registered an astounding 25 million users worldwide and was garnering over 2.2 billion page views monthly. That’s almost as much as The New York Times gets today. Users spent an average of six hours and 15 minutes on the site every month. Entertainment giant Viacom, which owned CBS and Nickelodeon, purchased the site from Adam, Donna, and Doug Dohring for $160 million.

But while Viacom technically owned the virtual community, its real caretakers were the users themselves. And in order to really contribute to this community, they had to have some skills beyond just figuring out how to access the internet.

A user’s Neopets page was like a profile page that was viewable by others. Users didn’t have to settle for the standard template, though. With some basic HTML skills, they could customize it. Having a more distinctive landing page gave users incentive to learn some basic coding skills they might not otherwise have been motivated to discover. Some players would even offer to build out web pages for other users in exchange for Neopoints. They were Neopian contractors.

The other edutainment aspect to Neopets was in its digital currency. The site had NEODAQ, a take-off of the NASDAQ stock market that updated the economy of Neopia in almost real time. Users could even invest their Neopoints in fake companies inside of the game and then watch as their fortunes grew or were wiped out by a sudden market shift. If you thought Balthazar’s Faerie Bottling Inc. would rise in value, you could take a chance and maybe experience something usually reserved only for adults—total financial ruin.

One player, Neelou Etesami, told The Ringer:

“As a fifth-grader, I had set up extensive spreadsheets in Excel to track Neodaq stock market prices daily so that I could pick up on stock patterns, and buy low, sell high. … I ended up becoming a neomillionaire fairly quickly this way, and my friends saw me as some sort of neopoint baron.”

The more items a virtual store sold, the better its stock price would get. Some Neopets users figured this out and then collaborated on buying items to drive stock prices up. Young adults would be trading stock tips in the same forums where kids would be role-playing their favorite animal characters in a forest.

Neopets wasn’t above introducing some artificial market fluctuations to keep things interesting, either. When Enron collapsed, Neopets thought it would be fun to bankrupt a few similar digital companies in the game.

Remember, this was the early 2000s, and Tamagotchi didn’t allow for much more than cleaning up digital pet droppings. Neopets imparting coding skills and stock market savvy was extremely cutting edge.

Eighty percent of Neopets users were under 18. About 40 percent were under 13. That meant a lot of kids were getting acclimated to weathering stock market storms in the hopes of becoming neomillionaires. Neopets had something no social network really had before—an economy.

And this could sometimes translate into actual money. A player named Claire Hummel applied for a real job with Neopets doing digital art. She was hired and spent seven summers working for the company. What Neopets didn’t know was that Hummel applied when she was just 14 years old, a fairly precocious age to be getting hired by a big tech company.

Neoscams

With tens of millions of users and a sprawling community, Neopets could seemingly do no wrong. But even a fictional economy can invite a host of scammers and other troublemakers.

If the site was holding a beauty contest for pets, someone might try to rig the vote so their ball of fur won. Some used their newfound coding skills to write scripts that would automatically purchase a hot new product from a store before anyone had a chance to buy it. Other users could replicate items, creating more inventory than the site’s administrators intended.

It got a little nastier than that, too. Phishing scams targeted kids, enticing them to fill out their login information so other users could swipe their Neopoints.

Administrators cracked down on these schemes as best they could. Some even kept a running total of how many illicit Neopoints they had seized like contraband during a police raid, with totals in the billions.

But for the most part, Neopets provided something rare online—a relatively safe and positive experience for its younger users. The site even weeded out profanity and objectionable language in messages, automatically replacing a word like sexy with stupid. Immersive advertising aside, Neopets was one of the safer online hubs of its era. And it also tried to maximize its profits in a variety of ways.

The Neopets Universe

Early on, Doug Dohring proclaimed Neopets could be something like Marvel or Disney, with a rich mythology that could be transported into other venues. A planned feature film never materialized, but there were plenty of other ways for Neopets to infiltrate impressionable young minds.

In 2006, General Mills introduced Neopets Islandberry Crunch, a fruity cereal that resembled Trix and was based on an object from the game. The box featured a species known as kougra, a blue-haired tiger kind of thing. Inside was a prize—a Neopets trading card.

Speaking of trading cards—Neopets got their own tabletop card game in 2003 courtesy of Wizards of the Coast, the company behind Magic: The Gathering. The Neopets were pitted in contests involving strength, agility, magic, and intelligence. The series didn’t really catch on, though, and was discontinued in 2006.

You could also pick up Neopets: The Official Magazine, a bimonthly publication. The first issue in 2003 featured a pretty salacious-looking fairy on the cover. Inside were games and product checklists to keep track of your virtual Neopets merchandise. It ran through 2008.

That same year, Jakks Pacific released a line of plush Neopets toys, which were sold exclusively at Target, but no one got into a Beanie Babies-style melee over them. A line of toy Neopets were offered at Burger King that year, too.

While all these ancillary products were fun, none of them made much of an impact. Neopets really lived online, where users could experience a fully immersive world. The concept seemed poised to become a permanent fixture on the internet. Yet you’re probably not caring for a four-legged creature named Poogle currently. What happened?

By 2011, Neopets had reached a staggering 1 trillion cumulative page views. But as the internet grew, visitors had more and more places to interact. The customization of Neopets became less and less of a novelty when compared to a Facebook profile. And that cool virtual economy? It also had some not-so-cool virtual inflation that made in-game items too expensive for a lot of players. With so much traffic, there was simply too much virtual cash floating around.

Neopets was sold in 2014 to an educational company named JumpStart. But the conversion was a little bumpy, and the site developed some defects and suffered a data breach affecting 70 million users. By 2016, some described the site as a kind of ghost town. The pets were abandoned, with users visiting the site less and less often. Pretty soon, only a few thousand people were coming on a regular basis to take care of their animals.

When JumpStart was acquired by a company named NetDragon in 2017, Neopets started to show some signs of life. New administrators began updating the site’s blogs and creating events for players to get involved with. That led to a surge of interest in people who had forgotten they even had a Neopets account. In a lot of cases, their digital pets were still there, waiting for them—alive and kicking and really, really hungry.

Of course, there were the expected controversies, too. In 2021, users were dismayed to see that some opportunistic players were creating black market fake versions of Neopets and selling them for actual money. These were Neopets that were considered out of circulation and extremely rare. Selling a fake version was a bit of a throwback to the old Neopets schemes. In a way, it was a sign the site and its community was still active. At last count, more than 283 million Neopets populate the site, and it has around 100,000 daily active users. While a far cry from their heyday, Neopets are nowhere near extinct.

The Neopets Legacy

So why did Neopets thrive? On one level, it had that Tamagotchi appeal—taking care of a digital pet was addictive. But Neopets had a lot more going on. Community members got lessons in coding and finance without even really realizing it—at least, not until they discovered they had been building skills that led them into programming or money management. Neopets may be the only computer game that hid its edutainment value almost completely. This wasn’t The Oregon Trail, and you didn’t have to play it in computer class at school. Neopets built some very grown-up ideas into a very simplistic interface. Remember 14-year-old digital artist Claire Hummel? She ended up working for Xbox, and is now with the video game company Valve.

It was also a training ground for the internet of today. Communities with specific interests? Neopets had it. Digital currency? They did it. Trolls, memes, fan art? It was all there. Neopets helped acclimate people to having virtual identities that coexisted with real life. In 2019, Allegra Frank, then associate identities editor at Vox, wrote that Neopets helped her with some disruptive social anxiety. She could bond with classmates over their Neopets and carry their friendships to and from the digital community.

Now Neopets are taking a page from the internet of today, offering NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, and heading into the Metaverse as a way of reviving interest. Whether or not those methods work, the Neopets legacy as a pioneering site that offered way more than virtual cats is already secured.

This story has been adapted from an episode of Throwback on YouTube. Subscribe to the Mental Floss YouTube channel for more cultural deep dives.