Before electromagnetic field detectors and infrared thermometers were used to measure paranormal activity, Shirley Jackson framed ghost hunting as a scientific endeavor in The Haunting of Hill House. Her novel opens with Dr. John Montague recruiting test subjects to stay at a supposedly haunted house for the summer. As a “man of science,” he hopes to record evidence of the supernatural that even skeptics can’t deny—though he’s careful not to label Hill House “haunted” before he has proof.

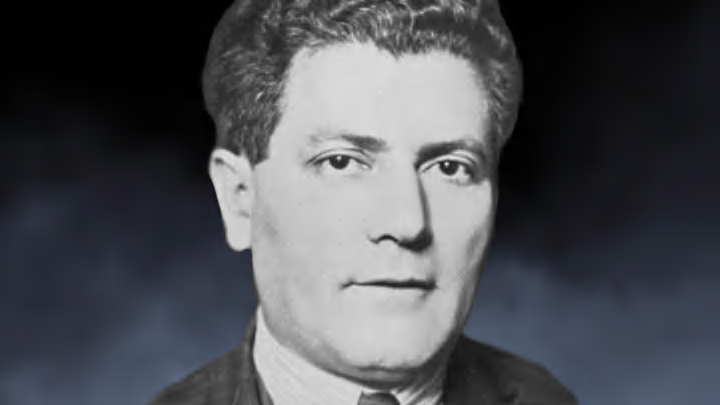

Jackson’s twist on the classic ghost story reinvigorated the genre in 1959, but her research-minded paranormal investigator wasn’t a wholly original invention. The author based Dr. Montague on investigators from real life, including Nandor Fodor, a parapsychologist whose work angered spiritualists, earned praise from Sigmund Freud, and garnered attention from Hollywood.

Explaining the Unexplainable

Alma Fielding desperately needed help. Beginning in early 1938, the 34-year-old homemaker reported experiencing weird phenomena in her home in the London suburb of Thornton Heath. She described glasses flinging themselves across rooms; soon, she claimed that objects like watches were jumping between her pockets. Mysterious scratch marks appeared on her back. Though her husband and son had witnessed the strange activity as well, it seemed to concentrate around Alma. Stolen rings magically slid onto her fingers while shopping and small animals materialized on her lap on car trips.

It was unclear whether the problem warranted a medium or a psychologist. Fortunately, Nandor Fodor had a foot in both worlds.

Fodor had been immersed in the paranormal scene for years by the time he crossed paths with Alma. Born in Hungary in 1895, he had a supernatural experience in his childhood, and this area of interest would shape the rest of his career: He worked as a journalist in London and New York, contributing articles on paranormal matters to spiritualist publications like the British journal Light; his most impressive achievement as a writer was penning the Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science, a 400-page tome hailed as being “of immense value to all psychic investigators and of infinite interest to the ordinary open-minded reader.”

Fodor didn’t have much trouble finding an audience for his work. Spiritualism was in the midst of a revival in the 1920s and ‘30s, and numerous groups dedicated themselves to the study of otherworldly matters. Fodor was a member of several of them—including the Ghost Club and the London Spiritualist Alliance. He eventually left journalism to fully immerse himself in this world, and by 1938 he was a research officer for the International Institute for Psychical Research.

But despite his prominent standing in these circles, Fodor didn’t always align with his peers. He often approached supposedly paranormal cases with skepticism; while many spiritualists were resistant to fresh ideas, he viewed the paranormal as a new frontier to be explored. He was living through an era of technological innovation and was frustrated that spiritualism was stagnant by comparison. “We have ceased to believe in technical impossibilities,” he wrote for the Leicester Evening Mail in 1934. “Yet as soon as it comes to psychological findings, to latent powers of the human soul, like a war-horse on the bugle call we charge into the field to fight.”

Fodor wasn’t afraid to be a pioneer in his field. This meant he was open to exploring theories that went against widely-held beliefs—like his idea that “ghostly” activity wasn’t connected to ghosts at all.

A Peculiar Poltergeist

Fodor was intrigued by newspaper reports of Alma Fielding’s haunting. Journalists called the force shooting eggs down hallways and shattering saucers a poltergeist, or an incorporeal entity capable of influencing the physical realm—often violently. Eager to learn more about such disturbances, Fodor decided to investigate her case.

Before meeting her, Fodor had a hunch that Fielding’s troubles were caused by something other than ghosts. Around the same time that spiritualism was experiencing its second wave in Britain, the field of psychology was undergoing a transformation. Freud had popularized the concept of an “unconscious mind” that expresses itself through involuntary means. Fodor was a fan of the psychoanalyst’s writings on repressed memories and their effects on the psyche, and he took the theory one step further. Maybe the destructive influence of buried trauma extended beyond the patient’s mind to the outside world. If that was the case, he believed such psychic disturbances would look a lot like what Fielding was experiencing in Thornton Heath.

Though he already had his hypothesis, Fodor studied Fielding with the rigor of a scientist working in a more respected field. He brought her to the International Institute for Psychical Research in London, where she was met with cameras, voice recorders, and X-ray machines—and according to his records, his subject gave him plenty of data to analyze. He took photographs of scratches on her arms that were supposedly inflicted by a spectral tiger and puncture wounds on her throat that she claimed came from a winged beast. When she told Fodor that a spirit had impregnated her in the night, he witnessed her belly expand. Other members from the institute were reportedly present in the room when, on various occasions, a mouse, a beetle, a bird, a lamp, and a brooch seemingly materialized from nothing.

In fact, X-rays showed that Fielding was hiding some of the objects inside or on her person; it was clear, as Fodor had suspected, that there was nothing supernatural about her case. But while she was “ruining her case by fraud,” as he would later write, Fodor ultimately believed that what they were witnessing was proof of the power of the unconscious mind—and evidence of his theory.

When strange happenings occurred around Fielding, she entered a trance-like state, which Fodor thought suggested the phenomena were originating with her (or her unconscious mind) rather than happening to her. He believed that the trauma Fielding had experienced in her life—from the loss of children to severe health issues—was causing her to unconsciously act out.

Not everyone was as thrilled by Fodor’s conclusion as he was. When members of the institute learned that he was exploring a psychoanalytical explanation rather than a psychical one, they were horrified. His ideas were radical and contradictory to the organization’s work, so they kicked him out.

While he was rejected by his spiritualist colleagues, Fodor found a warmer reception in psychoanalyst circles. Following his expulsion from the institute, Fodor’s wife Irene hand-delivered his report on the psychic poltergeist to Freud. Freud read the paper and responded in a letter, writing, “Your efforts to study the medium psychologically ... seems to me to be the right steps.” He said he found it “very probable” that his conclusion regarding the Fielding case was correct, and that was all the validation Fodor needed to continue pursuing his work.

Two decades later, in 1958, Fodor published a book about the Thornton Heath poltergeist titled On the Trail of the Poltergeist. In it, he argued that judging Fielding based on the logical and ethical measures put in place by society was the wrong way to look at the case:

“A dissociated woman is not necessarily bound by considerations of ethics and logic. She is not ruled by approved social instincts. She is governed by her unconscious mind, which has its own standards of conduct. By securing, regarding these particular phenomenon, evidence of deliberate fraud we have only exposed one of the many problems that arise out of her dissociation. As dissociation is due to an injury to the psyche which, in turn, gives rise to objective and subjective psychic phenomena, it is well within the province of psychical research to go further. Indeed, we are bound to do so if we wish to understand the case. If there was a psychological cause behind the phenomena which we are discussing, it is distinctly possible that for our subject a fraudulent phenomenon had exactly the same value as a genuine one. Her unconscious mind would not be interested in psychical research and in the laws of evidence. It would be solely concerned with its own troubles and, possibly, might economise with the forces at its disposal.”

Fodor’s theory as laid out in On the Trail of the Poltergeist never supplanted ghosts in popular culture—but it did get a major endorsement from the literary world the following year.

Ghost in the Machine

Despite its title, The Haunting of Hill House isn’t your typical haunted house tale. The old building is initially presented as the source of the odd events in Jackson’s book, but we soon see that the haunting is connected to—and perhaps caused by—one character in particular. In addition to the horror she encounters in Hill House, Eleanor Vance struggles with inner turmoil and a suffocating home life. As her anxiety worsens, so does the unearthly chaos around her.

The story of a poltergeist-plagued young woman at the center of a scientific paranormal investigation would have sounded familiar to anyone who had read Fodor’s work before opening Hill House. Like Fodor, Jackson entertained the possibility of mental disturbances expressing themselves as supernatural events in the physical world. The science to back up the concept was still lacking, but its power as a literary device was undeniable.

The novel has strong parallels to the Alma Fielding case, but that wasn’t Jackson’s original inspiration. The seed for Hill House was originally planted when Jackson picked up a book on 19th-century psychic researchers who, as she would later write, “rented a haunted house and recorded their impressions of the things they saw and heard … yet the story that kept coming through their dry reports was not at all the story of a haunted house, it was the story of several earnest, I believe misguided, certainly determined people, with their differing motivations and backgrounds ... I wanted more than anything else to set up my own haunted house, and put my own people in it, and see what I could make happen.” A derelict building she spotted from a train heading into New York City provided further fodder for her tale.

Then, in 1958, Jackson was working on the novel when she read newspaper reports of a Long Island family receiving unwanted attention from an alleged poltergeist. Like Fielding, the Herrmanns experienced objects in their home moving on their own, and the activity was linked to one resident in particular. In this instance, investigators named preteen Jimmy Herrmann as a potential focal point for the disturbances. (In addition to influencing Hill House, the Herrmann family is also credited as the inspiration for the movie Poltergeist 24 years later.)

When explaining the link between psychic power and poltergeist activity, the article about the case cited Haunted People, a book Nandor Fodor co-wrote with his fellow investigator Hereward Carrington. Shirley Jackson sought out the book to learn more about the theory.

“Even had she not acknowledged it to Fodor, its influence would be obvious,” Ruth Franklin writes of Haunted People in the biography Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life. Many aspects of the book are taken straight from Fodor’s research, including the inexplicable shower of stones raining from the sky Eleanor experienced at age 12. According to Franklin, this phenomenon is the “most frequent characteristic of a poltergeist manifestation” recorded in Haunted People: “The vast majority of poltergeist incidents cited in Haunted People have one element in common—an element that appears over and over in the long list of cases the book references, and that will be immediately obvious to any reader of Hill House.”

The Haunting of Hill House was successful enough to get a big screen adaptation four years after its release. The filmmakers wanted an advisor to bring a layer of realism to the fantastical tale, and Nandor Fodor was the obvious choice. While serving as the film’s consultant, Fodor met Jackson and asked her about her inspiration. She confirmed what he had suspected: Yes, she had read his writing on parapsychology. Clearly it had resonated with her.

Fodor and Jackson both died shortly after the film’s release—the former in 1964 and the latter the following year. Each left behind impressive bodies of work, but they’re best remembered for introducing the world to a different type of ghost story—one that swapped familiar ghosts with the horrors of the human mind.