In the past 20 years, the number of women-owned businesses has risen 114 percent. But female entrepreneurship isn't just a hallmark of the modern era: Since as early as the 17th century, women have been forging their own paths in a variety of trades. From merchants to ironmasters to dressmakers, these historic women shattered glass ceilings and broke stereotypes to rise to the top of their industries.

1. Margaret Hardenbroeck

When 22-year-old Margaret Hardenbroeck arrived in New Amsterdam (later New York) from the Netherlands in 1659, she was ambitious and ready to work. She already had a job lined up—collecting debts for a cousin's business. She continued to work even after she married the wealthy merchant Pieter de Vries, this time as a business agent for several Dutch merchants. She sold small goods like cooking oil to the colonists, and bought furs to send to Holland.

When Peter died in 1661, Hardenbroeck inherited his estate and took over his business. She expanded her fur shipping operations in Holland, trading the furs for merchandise to sell back in the colonies. For the Dutch, it was not wholly unusual for women to run businesses on equal footing with men; in New Amsterdam, they sometimes called themselves she-merchants. Hardenbroeck would become the most successful and wealthiest she-merchant in the colony.

Eventually, she was able to purchase her own ship, the King Charles, and accumulated real estate holdings throughout the colonies. Ever the savvy businesswoman, Hardenbroeck ensured that her wealth, properties, and independence were protected when she married her second husband, Frederick Philipse, by choosing an usus marriage under Dutch law. That meant she rejected marital guardianship of her husband and communal property, retaining all that was hers prior to marriage. When Hardenbroeck died in 1691, she was the wealthiest woman in New York.

2. Rebecca Lukens

In 1825, 31-year-old Rebecca Lukens found herself a widow and the new owner of Brandywine Iron Works and Nail Factory. The Pennsylvania-based company had been started by Lukens’s father Isaac Pennock in 1810, leased to her husband Charles, and ultimately left to her after both men died only a year apart. As uncommon as it was at the time for a women to be an ironmaster, and despite objections from her own family, Lukens took over and led the company into a new era of innovation and industry.

Under her husband’s leadership, Brandywine Iron Works had harnessed the demand for steam power by producing rolled iron plate for steam engines. Lukens continued this line of production and propelled Brandywine to become the leading producer of boilerplate. But she saw another opportunity for iron when the Philadelphia & Columbia Railroad, one of the first commercial railways in the U.S., launched in the mid-1830s, and she began seeking out commissions to produce iron for locomotives.

Even in the midst of the financial crisis of the Great Panic of 1837, Brandywine continued to roll out iron, and when business was stagnant, she sustained her employees by putting them to work maintaining and updating the mill. When she couldn’t pay them with money, she paid them with food. Her foresight and willingness to seek out new opportunities kept Brandywine afloat when other ironworks failed, and her business emerged from the Panic as the most prominent ironworks company. Lukens herself is remembered as the first woman CEO of an industrial company, and one of the first female ironmasters in the US.

3. Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley was one of Washington, D.C.'s most popular 19th century dressmakers—but it was a long and difficult road to financial independence and recognition. Born into slavery in Virginia in 1818, Keckley was moved from plantation to plantation. Taught sewing by her seamstress mother Agnes Hobbs, Keckley used this skill while still a teenager to build a clientele, making dresses for both white women and freed black women. While much of the money that she made from her dresses went to the family who owned her, some of her loyal clients loaned her the $1200 she needed to buy her and her son’s freedom. Keckley worked to pay back all the patrons who helped her buy her freedom before moving to Washington, D.C.

In D.C., word of her talents reached Mary Todd Lincoln. The first lady took Keckley on as her personal designer—and close personal friend. Keckley designed nearly all of Mary’s gowns during her time in the White House, including the dress she wore at Lincoln’s second inauguration, now on display at the Smithsonian. As a visible and well-respected free black woman, Keckley also founded the Contraband Relief Association (later the Ladies’ Freedmen and Soldiers’ Relief Association), an organization that raised money and provided food and clothing for black people and wounded Union soldiers.

Keckley’s success in D.C. ended, however, shortly after she published an 1868 autobiography—Behind the Scenes, Or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House. Mary saw the sections about her and the White House as a betrayal of confidence, and ended their friendship. The ripple effects ruined Keckley’s reputation in D.C. In the aftermath, she was offered a position at Wilberforce University in Ohio as head of the Department of Sewing and Domestic Science Arts, which she accepted. Keckley also organized the dress exhibit at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. She died in 1907.

4. Lydia Estes Pinkham

Lydia Pinkham reputedly came into possession of a secret medicinal recipe when her husband Isaac accepted the formula in lieu of money owed to him. The recipe contained five main herbs—pleurisy root, life root, fenugreek, unicorn root, and black cohosh—and alcohol. Pinkhman brewed her first batch of the soon-to-be-famous Vegetable Compound on her stove, and just three years later, she launched the Lydia E. Pinkham Medicine Co., a home remedy business run by and for women.

Pinkham claimed that her Vegetable Compound could cure a spectrum of female-specific ailments, from menstrual problems to a prolapsed uterus. She started out small, first distributing her compound to neighbors and friends, but in the midst of the financial crisis of 1873—when her husband was ruined—she began selling it and writing female health pamphlets to go alongside it. Her three sons helped her package, market, and sell the compound, and the strategic advertising campaign they implemented was key to the business’s success. She was the first woman to put her own likeness on her product, which helped create brand loyalty and spoke to her target audience: women. Eventually, she was able to expand her business beyond the U.S. and into Canada and Mexico.

There is little evidence proving the medical efficacy of Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound, and she is often lumped into the quackery category along with hundreds of other 19th century patent medicine producers. But she was also addressing a need for women-centered health care, which was often inadequate at the time. To find alternative methods of care, and avoid dangerous, expensive doctor visits, women often turned to home remedies—like Pinkham’s compound.

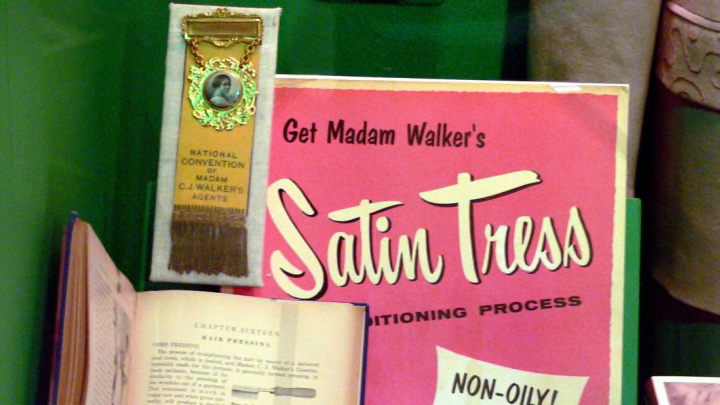

5. Madam C.J. Walker

Born Sarah Breedlove on a Louisiana plantation on December 23, 1867, Walker was the daughter of Owen and Minerva Anderson, freed blacks who both died by the time she was 7. She was married at 14, and soon gave birth to one daughter, Lelia. After her husband died only six years into their marriage, Walker moved to St. Louis, where she worked hard as a laundress and cook, hoping to provide a life free from poverty for Lelia.

In 1904, Walker began working as a sales agent for Annie Turnbo Malone’s hair care company—and soon came into some inspiration of her own. As the story goes, she had a dream in which a man told her the ingredients for a hair-growing tonic. Walker re-created the tonic and began selling it door-to-door. After she married Charles Joseph Walker in 1906 and renamed herself Madam C.J. Walker, she launched Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower, a line of hair care for black women.

Walker built a business that was earning $500,000 a year by the time she died, while her individual financial worth reached $1 million. Yet it isn’t the wealth alone that earned Walker a lasting legacy—it was how she used that wealth for a larger social good. Within her company, she trained over 40,000 black women and men and advocated for the economic independence of black people, particularly black women. She financially supported black students at the Tuskegee Institute, and contributed the largest recorded single donation, of $5000, to the NAACP, to support anti-lynching initiatives.

6. Annie Turnbo Malone

Though Madam C.J. Walker is often recognized as the first black woman millionaire, some historians say that credit belongs to Annie Turnbo Malone, the woman who hired Walker to sell her Wonderful Hair Grower in St. Louis before Walker started her own company. Like Walker, Malone’s parents were former slaves who died when Malone was young. Her older sister Peoria raised her, and together, they began experimenting with hairdressing.

Hair care products for black women were not widely produced, and the chemical solutions that were used often damaged hair. Malone developed her own chemical straightener around the turn of the century, and soon had created an entire line of other products for black women’s hair. In 1902 later, she moved to St. Louis and, along with three assistants, sold her hair care line door-to-door. She expanded the company rapidly, advertising in newspapers, traveling to give demonstrations at black churches, and even selling her line at the 1904 World’s Fair. In 1906, Malone trademarked her products under the name Poro, and in 1918, she built Poro College, a multi-story building that housed her business offices, training offices, operations, and a variety of public gathering spaces for the local black community. Malone even franchised retail outlets throughout North and South America, Africa, and the Philippines, employing over 75,000 women worldwide.

Malone’s company was worth millions, and she continuously used her money to improve the lives of those around her, either by hiring women or donating to colleges and organizations around the country. She made $25,000 donations to both Howard University Medical School and the St. Louis Colored YMCA. She donated the land for the St. Louis Colored Orphans’ Home and raised most of their construction costs, then served on their board from 1919 to 1943. In 1946, the orphanage was renamed in her honor, and it is still operational today as the Annie Malone Children and Family Service Center.

7. Mary Ellen Pleasant

When Mary Ellen Pleasant moved to San Francisco in 1852 she was fleeing the South, where she had been accused of violating the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. Pleasant had, in fact, broken the law—which punished anyone who aided people escaping slavery—as a member of the Underground Railroad, along with her first husband James Smith. For four years, Pleasant and Smith helped escaped slaves find new homes in free states and Canada, and when Smith died only four years after their marriage, Pleasant continued the work with a considerable inheritance from him.

When Pleasant moved to San Francisco in 1852 amid Gold Rush fever, she initially worked as a cook and housekeeper, but also began investing in stock and money markets, and lending money to miners and other businessmen in California's surging economy (at interest, of course). Pleasant was successful enough that she became a philanthropist, and continued her abolitionist work by housing escaped slaves and finding them jobs.

In 1866, Pleasant brought a civil rights case against the North Beach Mission Railroad Company, which refused to pick up black passengers. She won. Her success in court, as well as in continuing the Underground Railroad through her businesses, have earned her the title the mother of California’s civil rights movement.

By this time, Pleasant had amassed a sizable fortune and was considered one of the wealthiest women in America. But many people in white society saw her only as a black stereotype, and dubbed her Mammy Pleasant—a title she hated. She ended up being dragged into a series of scandals and court cases connected to wealthy men, accused of being both a thief and murderer. Financially drained and emotionally exhausted, she was forced to give up her home. The smear campaigns also greatly diminished her fortune and reputation in her time, but the legacy of her radical life has not been lost. In 2005, the city of San Francisco proclaimed February 10 Mary Ellen Pleasant Day in her honor.

8. Olive Ann Beech

From an early age, Beech knew how to manage finances. Born in 1903, she had her own bank account by the age of 7, and by 11 she had taken on the unusual childhood responsibility of keeping track of her family’s accounts. Already with a mind for business and finance, Beech enrolled in a business college in her home state of Kansas, where she studied stenography and bookkeeping. After college, she took a position in 1924 as a bookkeeper for Travel Air Manufacturing Company, a new commercial and passenger aviation company.

Beech was fundamental to the company’s growth, managing its correspondence, records, and financial dealings, and the organization quickly became the world’s largest commercial aircraft manufacturer. In a short time, she was promoted to office manager, and eventually became personal secretary to Walter Beech, one of Travel Air’s co-founders. Their working relationship became much more, and they married in 1930. As partners, they formed Beech Aircraft Company, and when Walter fell sick for a few months, Beech took over. With the onset of the U.S.’s entry into World War II, Beech Aircraft boomed, building over 7400 military aircraft over the course of the war.

When Walter died in 1950, Beech became president—the first woman president of a major aircraft company. She then took the company into the Space Age, establishing a research and development facility that supplied NASA with cryogenic systems, cabin pressurizing equipment for the Gemini program, and parts for the Apollo moon flights and Orbiter shuttle. Under Beech’s leadership, the company’s sales tripled.

In 1980, Beech Aircraft merged with Raytheon; Beech stayed on as chair of Beech Aircraft and was elected to Raytheon’s board of directors. Though Beech never piloted an aircraft herself, she was awarded the Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy that same year—the first woman to receive the award—for "five decades of outstanding leadership in the development of general aviation."