On September 11, 1851, a small farming community in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, fought what many consider the first battle of the Civil War. These neighbors united against slavery in the Christiana Resistance, a conflict that ended with the arrests of 141 abolitionists, both Black and white, and led to the largest treason trial in the history of the United States. The resistance was led by William and Eliza Parker, a married couple who had successfully freed themselves from slavery and dedicated their lives to building a community that could offer that same freedom to others.

"The Most Steadfast of Friends"

William and Eliza Parker both had escaped enslavement and built new lives in Christiana among the town’s largely anti-slavery Quaker population. One abolitionist neighbor described William as, “bold as a lion, the kindest of men, and the most steadfast of friends.” Because of Christiana’s location near the Maryland border, however, the area was plagued by people who made money by abducting freedom seekers and legally free people of color to sell them south. The Parkers formed a vigilance committee of local abolitionists; its members relayed intelligence to each other regarding area kidnapping activity and helped enslaved people passing through to escape to Canada on the Underground Railroad.

When word got out that Maryland enslaver Edward Gorsuch had arrived in Christiana with armed civilians, a deputy U. S. Marshal, and a warrant for the seizure of Gorsuch’s “property,” four Christiana men who had escaped Gorsuch’s enslavement came to the Parkers for help. Eliza and William secured them in their home while the vigilance committee met and spread word to be prepared to defend the Parker farm.

Shortly before dawn on September 11, 1851, Gorsuch’s party arrived at the Parker house. They were met with William’s assertion that they would fight to the death before surrendering. When Gorsuch tried entering the home, Eliza repelled him by throwing a fishing spear his way. She then went to the window and blew a horn used to alert their neighbors of such trouble. Gorsuch’s party opened fire to stop her, but she kept up the alarm, encouraging all in the house to stand against recapture, no matter the cost. When one of the men in the Parker home suggested surrender, William replied, “Don’t believe that any living man can take you.”

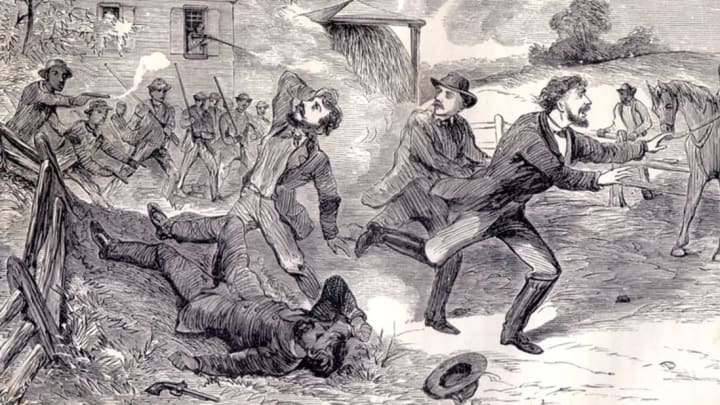

Neighbors were quick to arrive, many armed for defense. The Gorsuch party thought the white neighbors had arrived to help them, and were shocked to discover their error. William Parker and others tried to persuade Gorsuch and his men to leave without violence, but the latter insisted on having “his property.” Both sides opened fire. Before long, the Gorsuch party was either injured on the ground or fleeing with empty guns. One of the men Gorsuch had tried to recapture beat him with a rifle until he collapsed. As for Gorsuch’s death, per William’s memoir, “The women put an end to him.”

The white neighbors who had come to the scene now begged their Black neighbors to flee. Though their cause was just, a white man had died surrounded by armed Black men. They knew the chances of justice being served were abysmal. Still, the Parkers refused to head for Canada until after they made sure a doctor arrived to care for their injured adversaries.

The Fugitive Slave Act Stands Trial

Martial law was declared in Christiana. Nearly 150 people, Black and white, were placed under arrest. President Millard Fillmore soon received a telegram from Maryland Governor Louis Lowe, who threatened that his state would secede from the Union if the federal government did not seek justice for the murder of his constituent. Of the 141 men arrested, 39 were brought to trial on federal charges of treason. Prosecutors asserted that, on the basis of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, anyone aiding and abetting the flight of the enslaved from their enslavers was conspiring to defy federal law and dissolve the Union.

The initial trial was for Castner Hanway, the first white neighbor to answer Eliza’s alarm. The prosecution considered their case against Hanway the strongest of the 39, because popular opinion of the time was that only a white man could have organized an insurrection of this size. If they could convict Hanway, they would proceed with trying the rest.

Jury selection was complicated by the fact that nearly every person called asked to be excused from duty due to either ill health or poor hearing; one judge commented to a prospective juror, “your disease has become epidemic to-day.” On the witness stand, the deputy U.S. Marshal who had served Gorsuch’s warrant was caught in so many lies he was later tried for perjury. And when disputing the treason charge—which, according to the U.S. Constitution, involves levying war against the country—the defense attorney opted for a bit of sarcasm: “Armed with corn cutters, clubs, and a few muskets, and headed by a miller, in a felt hat, without a coat, without arms, and mounted on a sorrel nag, [those charged] levied war against the United States," he said. “Blessed be God that our union has survived the shock.”

By the time arguments closed, the jury only needed 15 minutes to declare Hanway “not guilty.” The federal prosecution had lost what they considered their strongest case. By the time Hanway and his companions had been sent back to Lancaster to face state murder charges, local politicians had realized the voting public was becoming sympathetic to the resisters, and a trial would destroy their chances of reelection. All 39 were released on December 31, 1851.

Frederick Douglass described the impact of “this affair at Christiana” as having “inflicted fatal wounds on the fugitive slave bill … for slaveholders found that not only did it fail to put them in possession of their slaves, but to attempt to enforce it brought odium upon themselves.” Within 10 years, the nation would be at war over that law and all laws that called people property. From his new home in Buxton, Canada, William Parker wrote his memoirs, sharing his hopes that, “Prejudice is fast being uprooted ... In a short time I hope the foul spirit will depart entirely.”