In November 1970, The Criminologist published an article by Dr. Thomas Stowell, an octogenarian surgeon with some thoughts about the identity of Jack the Ripper.

In his youth, Stowell was friends with Caroline Acland, the daughter of a royal family physician named Sir William Gull. According to Acland, her father had treated a young gay man with syphilis, which he had possibly contracted from a prostitute in the West Indies. By the late 1880s, the disease had spread to the patient’s brain, apparently inspiring him to exact revenge upon nearby prostitutes in London’s Whitechapel district. Gull began believing his patient was Jack the Ripper, and he conspired with the police commissioner to cover it up.

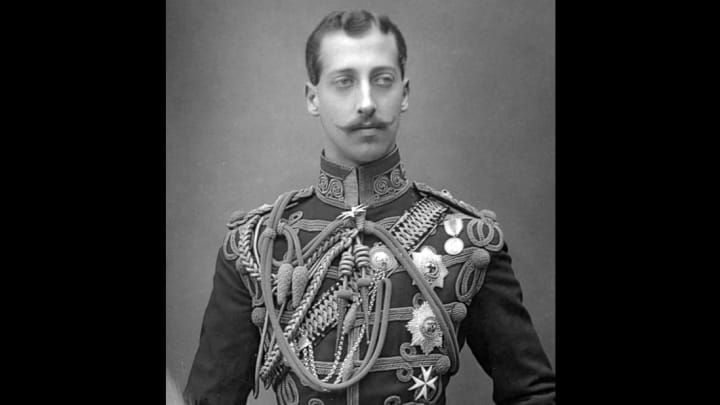

Stowell never named a suspect in his article, but he didn’t need to. Anybody with a cursory knowledge of British royal family history knew of a prince who fit the bill: Queen Victoria’s grandson, Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale.

Not only had rumors circulated about the prince's sexuality, but he also died of illness (influenza, not syphilis) in 1892, at just 28 years old. The media took the idea and ran with it, and Stowell appeared on the BBC to discuss his theory. Through all the publicity, however, he refused to point a finger at the prince. “I have at no time associated His Royal Highness the late Duke of Clarence, with the Whitechapel murderer or suggested that the murderer was of royal blood,” Stowell wrote to The Times.

Within weeks, Stowell was dead. His death itself wasn’t suspicious—he was in his late eighties at the time—but it did complicate matters. Almost immediately following his death, Stowell's son—Dr. T. Eldon Stowell—burned all documents related to his father's research on Jack the Ripper. “I read just sufficiently to make certain that there was nothing of importance,” Dr. Stowell told the press at the time. “The family decided that this was the right thing to do. I am not prepared to discuss our grounds for doing so.”

If Stowell had any concrete evidence from Gull’s journals or elsewhere, he took it to the grave. Furthermore, Prince Albert Victor had an alibi for a few of the murders. A Buckingham Palace official unearthed an issue of The Times from October 1, 1888, which reported that two women had been murdered in London the previous night. In the very same newspaper, it was mentioned that Prince Albert Victor had been at Balmoral Castle in Scotland on September 30. Based on other records from Buckingham Palace, it seemed likely that the prince had been with his family at Sandringham House on November 9, 1888, when another murder had occurred in London.

The media frenzy eventually faded, but Stowell was far from the last to suggest that Prince Albert Victor and Jack the Ripper were one and the same. As All That’s Interesting reports, Stephen Knight put forth a new theory in his 1976 book Jack the Ripper: Final Solution. The prince, Knight claimed, had wed a Catholic woman from Whitechapel and fathered a secret child. In order to keep this shameful offense under wraps, the royal family had conspired to kill any person who knew about it. Though Knight’s information had allegedly come from the grandson of Albert Victor and his anonymous wife, this theory—much like Dr. Thomas Stowell’s—failed to prove a single thing.