As recent graduates start exploring the job market, they should take comfort in the fact that these noteworthy authors—featured in Mental Floss’s new book, The Curious Reader: A Literary Miscellany of Novels and Novelists, out now—took a sometimes winding path to literary superstardom.

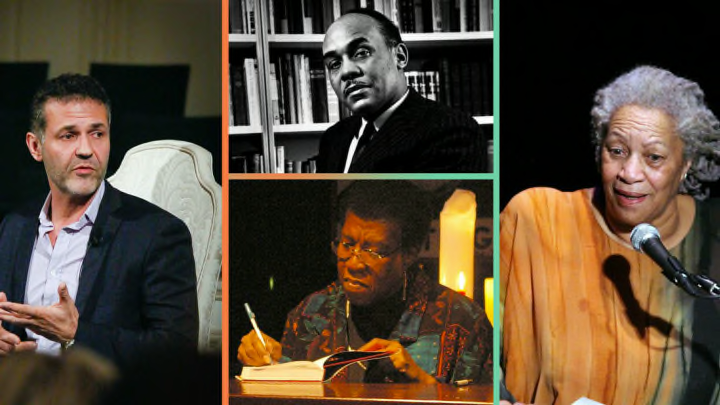

1. Khaled Hosseini

When 15-year-old Khaled Hosseini came to the United States as a refugee from Afghanistan in 1980, he only knew a few words of English—and though he wanted to be a writer, “it seemed outlandish that I would make a living writing stories in a language I didn’t speak,” he told The Atlantic. So he eventually chose a more “serious” profession, becoming a doctor. Later, he wrote what would become his first novel, The Kite Runner, in the mornings before going to work as an internist at a hospital in Los Angeles. That hard work paid off: The Kite Runner was a huge success, paving the way for more novels. Hosseini hasn’t practiced medicine since 2004.

2. Octavia Butler

Raised primarily by her grandmother and widowed mother, Octavia E. Butler grew up in Pasadena, California, poor, dyslexic, and painfully shy. Published Black women writers were rare in 1950s America—and Black women science fiction writers even more so—but that didn't keep Butler from recognizing her own potential. While watching the B-movie Devil Girls From Mars (1954) at age 12, she realized that she could write something better than that film. “The clincher,” she later recalled, was when she realized that “somebody got paid for writing that awful story.”

Butler enrolled in Pasadena City College and earned an Associates of Arts degree in 1968. Though her mother encouraged her to find steady work as a secretary, Butler preferred jobs that left her with enough mental energy to wake up early every morning and write. These odd jobs included dishwasher, telemarketer, and potato chip inspector. She also continued her education past undergraduate school, attending the Clarion Science Fiction Writers’ Workshop at the recommendation of her mentor and fellow science fiction writer Harlan Ellison. In 1976, she published Patternmaster, the first book in the Patternist series. Her 1979 novel Kindred, about a Black woman in modern-day California who is sent back in time to a pre-Civil War Maryland plantation, cemented her legendary reputation in the speculative fiction world.

3. Jack London

One of the most popular American novelists at the turn of the 20th century, Jack London’s tales of adventure and survival mirrored his real life. As a teenager, London worked as an oyster pirate, then an oyster pirate catcher, and later he joined a ship bound for the north Pacific. London joined the Klondike Gold Rush in 1897, but didn’t strike it rich until he turned his Yukon experience into novels and short stories. He published The Son of the Wolf in 1900. His best-known novel, The Call of the Wild (1903), became an instant bestseller.

4. Ha Jin

Ha Jin didn’t think he’d become a writer. In the 1970s, he followed in his father’s footsteps, enlisting in the People’s Liberation Army; he was just 14, but lied about his age. After his time in the military, he worked at a railroad company, where he learned English, and three years later, he finally went to college. (“During the Cultural Revolution, no colleges were open,” he once explained. “So for 10 years we couldn’t go to college—hence the big interruption.”)

Jin, whose real name is Xuefei Jin, studied American literature and got his master’s, then came to the United States to study in 1985. His goal was to return to China and teach American literature, but that all changed four years later, when he watched from afar as the Chinese Army fired on student protestors in Tiananmen Square. It was then that his life as a writer began: He decided to stay in America, and write only in English, publishing poetry and short story collections before releasing his first novel, In the Pond, in 1998, followed by 1999's Waiting, which won the National Book Award.

5. Mark Twain

Samuel Clemens’s “school days ended when he was 12,” according to The New York Times. His first job, working as a printer at local newspapers, may have spoken to an interest in letters, but it was his next position, as a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi River, that led most directly to his later literary work, especially in his memoir, Life on the Mississippi. His time on the river could have also given Clemens his pen name, Mark Twain—a moniker that would earn great renown, first as the author of humorous short stories like “Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog,” and later for his pivotal contribution to American literature, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

6. George R.R. Martin

As a comic book-obsessed kid, George R.R. Martin realized that he could probably write better stories than what appeared in many fanzines after he got a letter published in an issue of Fantastic Four. He released The Armageddon Rag in 1983, but the reception to the novel was so terrible that Martin switched gears—and mediums—entirely, writing for The Twilight Zone reboot and the live-action Beauty and the Beast television series starring Linda Hamilton and Ron Perlman. It was while working in television that he began writing the book that would become A Game of Thrones, the first volume in his yet-to-be completed A Song of Ice and Fire series. The first book wasn’t a bestseller, but the subsequent books in the series took off: They sold more than 90 million copies and were adapted into HBO’s juggernaut series Game of Thrones.

7. Toni Morrison

Toni Morrison’s first novel, The Bluest Eye, was written in the limited free time available to her between her day job in the publishing industry and the responsibilities of raising two children. Perhaps the dueling pressures of these two worlds lent her unique insight into “the role women play in the survival of … communities,” as The New York Times described an enduring theme of hers upon her death in 2019. Morrison’s first job after receiving her graduate degree was in academia, teaching at Texas Southern University and then at Howard. She returned to teaching intermittently even after her success as a writer.

8. Frank Herbert

Frank Herbert was a veteran newspaper reporter when he began circulating Dune, his 1965 novel of galactic intrigue over spice. Though it was well-received by sci-fi fans and even serialized in Analog magazine, Herbert had no takers until it was accepted by automotive publisher Chilton. By 1972, Herbert had given up his newspaper career to write novels.

9. Amy Tan

After stints at five different colleges, Amy Tan graduated with degrees in English and linguistics and worked as a language development specialist before turning to freelance business writing. Becoming a novelist was the furthest thing from her mind, but Tan did have an interest in short fiction and attended a writer’s group led by Molly Giles. Tan’s short stories led to what would become The Joy Luck Club, published in 1989.

10. Ralph Ellison

If not for the Great Depression—and Richard Wright—Ralph Ellison might have been a musician instead of a writer. Ellison picked up the cornet when he was 8 and later began playing the trumpet; at 19, he started studying music at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. In 1936, he headed to New York in order to raise funds for his final year of school and decided to stay. There, he was taken under the wings of celebrated writers like Richard Wright and Langston Hughes. Wright was editing a magazine at the time and had Ellison write a review, and, after that, a short story. (It was accepted, but got bumped for space just before the magazine went out of business.) The Depression raged, and Ellison headed to Ohio, where he hunted game and sold it to get by. At night, he wrote and studied writers like Joyce and Hemingway.

Ellison never went back to school, but he did go back to New York, and more short stories and essays followed. So did Invisible Man, published in 1952—and then a 40-year dry spell in which Ellison wrote essays and prose but was unable to finish Juneteenth. (It was published posthumously in 1999.) Ellison rounded out his days as a teacher and professor at a series of colleges and universities.

11. Kazuo Ishiguro

Kazuo Ishiguro, who played piano from the age of 5 and picked up the guitar when he was 15, initially thought he’d be a musician, not a writer—but it wasn’t meant to be. He had many meetings with A&R representatives, but as he recalled to The Paris Review, “After two seconds, they’d say, ‘It’s not going to happen, man.’” Ishiguro also worked at a homeless shelter and as a grouse beater for the Queen Mother at Balmoral, but it was in fiction where he found success: He published his first novel, the Nagasaki-set A Pale View of Hills, when he was 27, to critical acclaim.

12. Stieg Larsson

As a boy, Stieg Larsson honed his authorial prowess in notebook after notebook (and, finally, on a typewriter his father purchased for him). Though he did pen one adventure novel as a preteen, Larsson’s interest in writing was mainly journalistic. By his mid-twenties, he had served his compulsory 14 months in the national army, trained Eritrean revolutionaries in Ethiopia, and committed himself to combating Sweden’s lingering wave of right-wing radicalism through his own socialist, antifascist writing. Larsson took a job at a graphic design firm and spent every spare moment composing articles for leftist publications like Britain’s Searchlight. In 1995, he helped found his own: Expo. Then, in 2002, he decided to author a fictional series, hoping that its success would help fund his other endeavors. But while The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and its two sequels did achieve international acclaim, Larsson himself didn’t live long enough to reap the benefits—he died of a heart attack at age 50, before any of his books were published.

For more incredibly interesting facts about novelists and their works, pick up our new book, The Curious Reader: A Literary Miscellany of Novels and Novelists, out now!