Most people have only ever seen a genuine Egyptian mummy in a museum; fictional mummies, of course, are all over film, literature, and Halloween costume stores. But in centuries past, mummies were put to a variety of inventive uses: for art and commerce, science and entertainment, and possibly even to provide paper.

Many of these uses and abuses stemmed from the Egyptomania that gripped Europe and America throughout the 19th century, set off by Napoleon’s invasion of the country in 1798 and nourished by a string of amazing archeological discoveries. By the 1830s, upper-class Western Europeans and Americans began flooding Egypt in search of treasure, and mummies became a chief prize—treated as a symbol of the entire country’s exotic allure, and the “mysteries of the Orient“ more generally. The mummy madness progressed to the point where, Egyptologist Beverley Rogers notes, in 1833 a monk named Father Géramb remarked to the then-ruler of Egypt, Mohammed Ali, “it would be hardly respectable, on one’s return from Egypt, to present oneself in Europe without a mummy in one hand and a crocodile in the other.”

Read on for some lessons in just how disturbingly inventive these tourists could be.

1. People used mummies as medicine.

Strange as it may seem, people in early modern Europe frequently practiced a kind of cannibalism for health. According to historian Richard Sugg, “Up until the late 18th century, the human body was a widely accepted therapeutic agent. The most popular treatments involved flesh, bone, or blood, along with a variety of moss sometimes found on human skulls.“

Mummy, often sold as “mummia” (a confusing word that also refers to the bitumen with which mummies were embalmed), was applied to the skin or powdered and mixed into drinks as a treatment for bruising and other ailments. The belief may have come from ancients such as Pliny the Elder, who wrote that the bitumen used to embalm mummies offered healing powers. Sugg says that adherents included the French King Francis I, as well as Francis Bacon, who wrote that “mummy has great force in staunching of blood.” Mummia became such big business that there was a trade in fake mummies—made from executed criminals, slaves, beggars, and camels—just to keep up with demand, much like today’s market for counterfeit pharmaceuticals.

2. People used mummies at parties.

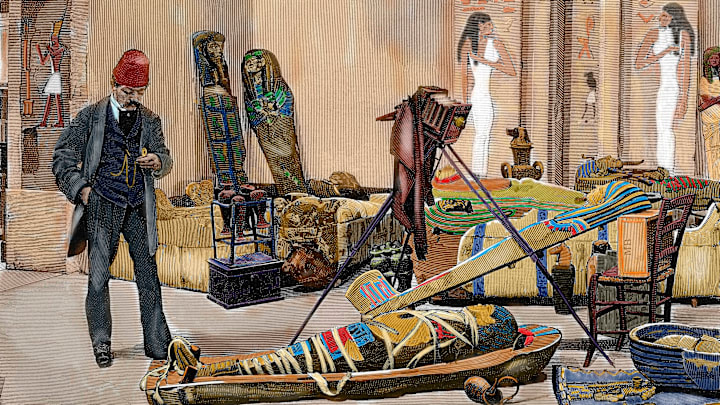

Need a theme idea for your next get-together? Why not take a page (or a rag?) from the Victorians and hold a mummy unrolling party, which is exactly what it sounds like. While the craze is sometimes overstated—it’s not like every aristocrat watched Tutankhamen’s cousin unwrapped over sherry in his drawing room—these parties were a not-uncommon feature of 19th century British life, especially among those who fancied themselves the more scholarly sort.

According to Rogers, mummy unwrapping as a social event really got going in Britain starting in the 1820s, thanks to a circus performer-turned-antiquities salesman named Giovanni Belzoni, who had made a name for himself in Egypt-obsessed circles after arranging for the removal of several massive Egyptian artifacts on behalf of British consul to Egypt Henry Salt. In 1821, he held a public mummy unwrapping as part of an exhibition of Egyptian antiquities near Piccadilly Circus. The event proved an enormous success—over 2000 people attended on opening day alone. One member of the audience was London surgeon and scholar Thomas Pettigrew, who was so enamored of the spectacle he began holding his own public, ticketed unrollings, usually with an accompanying lecture.

While there was occasionally an element of serious science (Pettigrew went on to write the first book on mummy studies, A History of Egyptian Mummies, in 1834, and earn the nickname “Mummy Pettigrew”), the gawk-factor was usually a larger draw. Not only were the mummies themselves fascinating (if a bit pungent), their wrappings often contained valuable talismans and amulets lying in and around the body.

Members of the upper class copied Pettigrew, and the idea spread, with unwrapping events held both at large venues and in private homes. According to Rogers, “Often the mummy came from the host’s own collection and invitations were such as those issued by Lord Londesborough in 1850, who promised a ‘mummy from Thebes to be unrolled at half-past two.’“ Consider it the Victorian version of unboxing.

3. People used mummies as paint pigment.

It sounds like an urban myth, but it isn’t: starting around the 16th century, a pigment called mummy brown, made from ground-up mummies, was a popular choice for European artists. Delacroix used it, as did British portraitist Sir William Beechey, and it was a special favorite of the Pre-Raphaelites. According to scholar Philip McCouat, in 1712 “an artist supply shop rather jokily called ’A La Momie’ opened in Paris, selling paints and varnish as well as powdered mummy, incense and myrrh.“ To be fair, not everyone knew what they were painting with. When artist Edward Burne-Jones found out, he held a little funeral for a tube of paint in his back garden.

4. People used mummies as interior decor.

Trips to Egypt were so popular among the upper classes of the 19th century that mummies were often displayed back home as souvenirs, usually in the drawing room or study, and occasionally even in bedrooms. Rogers notes that mummy hands, feet and heads were frequently displayed around the house, often in glass domes on mantelpieces. (The writer Gustave Flaubert was even known to keep a mummy’s foot on his desk.) Mummies were displayed at businesses, too: One Chicago candy store reportedly attracted customers in 1886 by showing off a mummy said to be “Pharaoh’s daughter who discovered Moses in the bulrushes.”

5. People may have used mummies for paper.

This a contentious issue among those who study the history of papermaking, but according to some scholars, paper mills on the East Coast of the United States imported mummy wrappings as source material during the mid 19th century. (It’s not quite as crazy as it might sound: A boom in printed materials vastly increased America’s appetite for paper in the early 19th century, and wood pulp was only introduced after a rag shortage in the 1850s. Mummies, meanwhile, were relatively plentiful.) The story is debatable: sources are vague, and while historians have discovered newspapers and broadsides that claim to be printed on mummy wrappings, the claim isn’t bullet-proof: It could be a joke, or, as often the case with mummies, a crafty publicity gimmick.

By the way, a related story that mummies were burned for railroad fuel is almost certainly a joke dreamed up by Mark Twain. In The Innocents Abroad, Twain described Egyptian railroad companies using fuel “composed of mummies three thousand years old, purchased by the ton or by the graveyard for that purpose,” and reported that “sometimes one hears the profane engineer call out pettishly, ‘D—n these plebeians, they don’t burn worth a cent—pass out a King!’”

6. People used mummies as stage props.

Mummies are a familiar symbol of romantic ghastliness in literature and horror movies, of course, but their use in stage magic is less well known today. Yet the same sense of exoticism and dread that made them work so well onscreen also made them effective as stage props. It didn’t even matter whether they were real.

In the 1920s, an elaborate fake known as “The Luxor Mummy“ appeared in stage shows with a magician named Tampa. According to The New York Times, the mummy originally belonged to vaudeville theatre owner Alexander Pantages, “who claimed that it was a seer and prophet named Ra Ra Ra.“ When the mummy “performed“ with Tampa, it would answer questions communicated through a telephone-like device. (No word on how an ancient Egyptian was able to speak English.)

7. People used mummies for fertilizer.

Animals were mummified by the millions in ancient Egypt to provide offerings for the gods and goddesses. Ibis and baboons were sacred to Thoth, raptors to Horus, and cats to the goddess Bastet. Cat mummies were particularly plentiful—so plentiful, in fact, that in the late 19th century, English companies bought them from Egypt for agricultural purposes. By one account, a single company purchased about 180,000 cat mummies weighing 19 tons, which were then pulverized into fertilizer and spread on the fields of England. One of the skulls from that shipment now resides at the natural history department of the British Museum.

8. People used mummies as fake relics.

After Joan of Arc was burned at the stake in 1431, her executioners were determined that no trace of her would remain—they burned her body a second time, then dumped what was left in the Seine. But in 1867, a jar labeled “Remains found under the stake of Joan of Arc, virgin of Orleans,“ turned up in the attic of a Paris pharmacy. It was recognized by the church as genuine, and later put on display at a museum run by the Archdiocese of Tours. However, in 2007, tests conducted by forensic scientist Philippe Charlier revealed that the contents of the jar predated Joan by thousands of years: They were actually a human rib and a cat femur, both from ancient Egyptian mummies.

9. People used mummies for fundraising.

Massachusetts General Hospital was the site of the first public surgery using modern anesthetic, which took place in 1846 in an amphitheater that became known as the Ether Dome. But the place is also home to something you don’t usually see in a hospital—an Egyptian mummy.

The well-preserved Padihershef arrived at Massachusetts General in 1823 as a gift from the city of Boston. The mummy had originally been given to the city by a Dutch merchant in the early 19th century (he reportedly purchased it to impress his in-laws), and the city gave it to the then-fledgling Massachusetts General Hospital to help it raise funds. Padihershef was put on display at Mr. Doggett’s Repository of Arts in Boston, where people paid $0.25 to see the one of the first complete human Egyptian mummies in the U.S. Padihershef then went on a year-long East Coast tour to raise even more cash for the hospital, before taking his place in the Ether Dome in time to witness the history-making surgery on October 16, 1846. He’s still there today.

A version of this story originally ran in 2015; it has been updated for 2022.