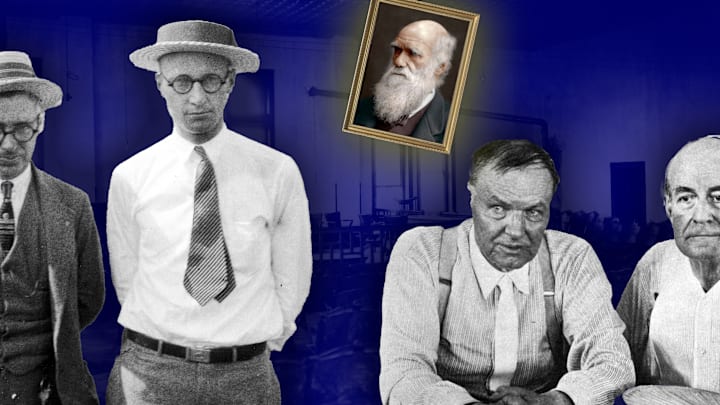

The State of Tennessee v. John T. Scopes, better known as the Scopes Monkey Trial, marked a turning point in American academic freedom and First Amendment rights in July 1925. The case challenged a Christian fundamentalist law enacted in Tennessee barring public school teachers from teaching the theory of evolution—and the sensational trial became an era-defining showdown between fact and faith.

Complete with celebrity lawyers, a media frenzy, and a live chimp, the Scopes Monkey Trial catalyzed a national debate still raging today. Here are 10 key facts from the trial that (symbolically) put Charles Darwin on the stand.

- The case challenged Tennessee’s Butler Act.

- The trial was imagined as a publicity stunt.

- Scopes wasn’t even sure if he’d taught evolution when he agreed to be a defendant.

- Dayton became a circus—with an actual monkey.

- It was the first trial broadcast live on the radio.

- Darrow put William Jennings Bryan on the witness stand.

- The same jury probably wouldn’t be called today.

- Scopes was found guilty.

- William Jennings Bryan died just days after the trial ended.

- After the trial, Scopes became a geologist.

- No other teachers were prosecuted under the Butler Act.

- What was the Scopes Monkey Trial’s location?

- When was the Scopes Monkey Trial?

- Who were the key players in the Scopes trial?

- Who won the Scopes Monkey Trial?

- Were any actual monkeys involved in the Scopes Monkey Trial?

The case challenged Tennessee’s Butler Act.

Tennessee lawmaker John Washington Butler presented his namesake act to the state House of Representatives in early 1925. The legislation prohibited educators from teaching evolution in public schools. Instead, they were instructed to teach Creationism, which alleges that God created the world in just six days (and rested on the seventh).

The Butler Act applied not only to elementary and high schools, but also to public university teachers, carrying a fine between $100 and $500 (roughly $1800 to $9200 today) and a misdemeanor charge for each violation of the act’s provisions.

The act passed on January 28, 1925 with 71 House members voting in favor and five voting against. After being approved by the Senate, the bill was signed into law by Governor Austin Peay on March 21, 1925.

The trial was imagined as a publicity stunt.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) put out an ad offering to defend any teacher willing to defy the Butler Act, thereby setting up a test case to demonstrate its violation of the First Amendment (“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion”).

Seeing the ad in Dayton, Tennessee’s local newspaper, Cumberland Coal and Iron Company manager George Rappleyea—no fan of religion—saw an opportunity to draw national attention to his small, rural town. He felt the controversy that would surely surround the trial could put Dayton in the spotlight and reinvigorate its floundering economy. He got Dayton public schools superintendent Walter White, local attorney Sue Hicks, and other leaders of the community on board with his idea during a meeting at Robinson’s Drugstore on May 5, 1925.

Then, Rappleyea approached local teacher John Scopes about breaking the law.

Scopes wasn’t even sure if he’d taught evolution when he agreed to be a defendant.

Scopes, who had moved to Dayton in the fall of 1924 from Kentucky, mainly taught math and physics in addition to coaching the school’s football team. Scopes had served as a substitute biology teacher, but never taught it full time, and he didn’t remember if he’d ever touched on evolution before.

He agreed to the trial as a favor to Rappleyea. Though he didn’t feel particularly strongly about evolution, Scopes supported academic freedom, and presumed he would be in no serious legal jeopardy by signing on a defendant.

Dayton became a circus—with an actual monkey.

The trial attracted two celebrity legal minds. Clarence Darrow, who would defend Scopes, was probably the most famous attorney in America; he had defended the notorious murderers Leopold and Loeb the previous summer in what was then called “the trial of the century.” Former Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, a legendary orator and devout Christian, served as the special prosecutor in the Scopes case.

On top of the attention Darrow and Bryan brought, the case’s scandalous premise and the ensuing media frenzy temporarily turned the town of Dayton into a spectacle. Local businesses cashed in on the crowds gathering for the opening arguments by selling commemorative “Monkey Trial” plates, cups, and ashtrays alongside stuffed monkeys and postcards depicting chimpanzees. At one point, an actual chimpanzee named Jo Mendi, a well-known vaudeville star, was brought to town to bolster the case’s publicity.

It was the first trial broadcast live on the radio.

Radio was still new in 1925, and the idea of broadcasting from the scene of the action was revolutionary. An announcer from Chicago’s WGN-AM broadcast live from Dayton and gave listeners a near play-by-play account of the events in the courtroom as they unfolded. Audiences heard the judge and attorneys arguing their cases, made possible by four microphones placed around the courtroom.

Bevies of newspaper reporters from across the country descended on Dayton as well, but the reporter who really captured the absurdities of the undertakings was Baltimore Sun journalist H.L. Mencken. In his dispatches from the courtroom, he mocked the Creationist arguments, coined the Monkey Trial epithet, insulted the local residents as “hillbillies,” and lampooned Dayton’s sanctimony:

“It would be hard to imagine a more moral town than Dayton. If it has any bootleggers, no visitor has heard of them. Ten minutes after I arrived a leading citizen offered me a drink made up half of white mule [moonshine] and half of Coca-Cola, but he seems to have been simply indulging himself in a naughty gesture. No fancy woman has been seen in the town since the end of the McKinley administration. There is no gambling. There is no place to dance. The relatively wicked, when they would indulge themselves, go to Robinson’s drug store and debate theology.”

While Mencken’s hot takes survive, no recordings of the radio broadcasts exist due to the limitations of the technology used at the time.

Darrow put William Jennings Bryan on the witness stand.

In one of the case’s most dramatic turns, the Scopes defense team called the prosecutor William Jennings Bryan to testify as an expert witness on the Bible.

Though Bryan would also serve as a witness for the prosecuting attorneys, lead defense attorney Darrow’s decision to cross-examine the elder statesman was a turning point in the trial’s public perception. Bryan, a three-time Democratic presidential nominee, faced intense questioning from Darrow when it came to the prosecution’s literal interpretation of the Bible’s creation story. For over two hours, Darrow interrogated Bryan about the veracity of other biblical concepts like Noah’s Ark and the Tower of Babel before his questioning was cut short by Judge John T. Raulston. The judge later ruled that the whole line of questioning was irrelevant and struck it from the record, and Bryan lost out on his opportunity to cross-examine Darrow in the same manner.

The same jury probably wouldn’t be called today.

Tennessee law did not allow female jurors until 1951, and Black men were largely prevented from serving on juries due to structural discrimination. Thus the jury for the Scopes trial was made up entirely of white men, and all but one was associated with a religious congregation, making it difficult to imagine they weren’t already swayed in favor of the prosecution. Some jurors admitted to believing in Creationism and were still allowed to serve.

Many members of the press (particularly from northern states) dismissed the homogenous jurors as simpleminded bumpkins, stoking resentment among Dayton’s residents.

Scopes was found guilty.

John Scopes, the actual defendant in the whole thing, did not have much of a chance of acquittal. After the trial concluded on July 21, 1925, the jury deliberated for just nine minutes before handing Judge Raulston a guilty verdict. Scopes was sentenced to a $100 fine (roughly $1800 today), the minimum allowed under the Butler Act.

Later, his conviction was overturned when it came to light that Judge Raulston, not the jury, determined the amount of the fine—essentially allowing Scopes’s case to be thrown out on a technicality. The Butler Act was still judged constitutional, but Tennessee law at the time required a jury to determine any fines above $100, so the Tennessee Supreme Court reversed the original trial’s outcome.

William Jennings Bryan died just days after the trial ended.

Bryan died from apoplexy (a.k.a. hemorrhagic stroke) on July 26, 1925, less than a week after his controversial victory in the Scopes Monkey Trial. Despite his commendable political career, Bryan’s legacy was clouded by the sensational trial and punishing moral debate in his final days. He was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia with his epitaph reading, “Statesman. Yet friend to truth! Of soul sincere. In action faithful and in honor clear.”

After the trial, Scopes became a geologist.

Scopes tried to escape the massive media attention and left his teaching position in Dayton. He enrolled in graduate school at the University of Chicago to study geology, then took a job as a petroleum engineer in Venezuela before returning to the United States and settling with his family in Louisiana. Although the case had a profound impact on American history, he told the Saturday Evening Post in 1943 that “usually I just don’t think about it.”

Scopes lived the remainder of his life in relative anonymity, only reemerging in the public consciousness in 1967 when he published Center of the Storm: Memoirs of John T. Scopes. He passed away from cancer in October 1970 at age 70.

No other teachers were prosecuted under the Butler Act.

Scopes remains the only teacher ever prosecuted under the Butler Act. The law remained in effect for decades following the Scopes Monkey Trial before being challenged by another Tennessee science teacher, Gary L. Scott, in the late 1960s. After Scott was fired from Jacksboro High School for teaching evolution, he sued to have his position reinstated, claiming the law violated his First Amendment rights.

Shortly after Scott filed the lawsuit with the backing of the ACLU, the state House and Senate passed legislation to repeal the Butler Act, and then-Governor Buford Ellington made it official on May 18, 1967. Scott was rehired at Jacksboro High School and awarded back pay.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Scopes Monkey Trial

What was the Scopes Monkey Trial’s location?

The trial took place at the Rhea County Courthouse in Dayton, Tennessee. Today part of the building is a museum telling the story of the Scopes trial and its impact on the town.

When was the Scopes Monkey Trial?

The trial began on July 10, 1925 and lasted 12 days. The jury delivered the verdict on July 21, 1925.

Who were the key players in the Scopes trial?

John T. Scopes was indicted for violating the Butler Act and was the defendant in the trial. His defense team was led by the famous attorney Clarence Darrow. The prosecution was led by former presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan.

Who won the Scopes Monkey Trial?

The jury decided for the prosecution and found Scopes guilty of violating the Butler Act. He was fined the minumum penalty of $100. His conviction was later thrown out on a technicality.

Were any actual monkeys involved in the Scopes Monkey Trial?

Nope! Baltimore Sun journalist H.L. Mencken, who coined the trial’s nickname, was referring to its debate over Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, which suggests that humankind evolved from earlier primates.

Discover More History: