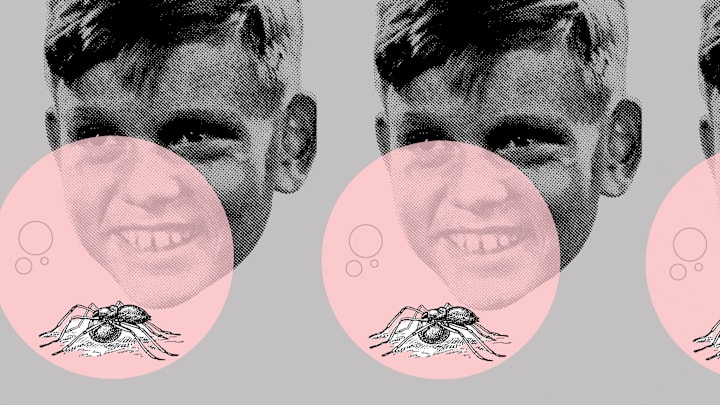

A lot of popular consumer products keep their recipes under a veil of secrecy. The Coca-Cola formula is said to be known only to a select few; KFC won’t disclose its 11 herbs and spices. But for a time in 1977, Bubble Yum had to go on the record and refute allegations that the key to their chewing gum’s success was courtesy of a very non-FDA-approved addition: spider eggs.

The urban legend began shortly after manufacturer Life Savers, Inc., introduced the gum nationally in 1976. Though bubble gum had existed for some time—it was invented by Fleer Corporation employee Walter Diemer back in 1928—this type of gum was soft and easy to masticate. Bubbles could be blown and popped in record time.

Mack Morris, then the president of Life Savers, decided to make the gum the star, rather than rely on novelties like other gum peddlers. “We felt they were mainly selling baseball cards and jokes rather than bubble gum,” he said.

Bubble Yum was tested in Phoenix, where both kids and adults responded positively. Adults belonged to a demographic that Morris called “closet chewers.”

With wider distribution, Bubble Yum was an immediate hit. Sales took off to the point that Life Savers began experiencing production shortages, prompting the company to take out ads apologizing for the lack of supply. The Chicago Tribune reported that kids operated a black market of gum, selling the hard-to-find product, which retailed for 20 cents per pack, for $1 or more. Once responsible for just 10 percent of chewing gum sales in 1970, bubble gum would rise to command 33 percent by 1978.

For Live Savers, Bubble Yum was looking like a runaway hit. But then kids began to talk.

The Bubble Bursts

The first sign of trouble appeared to originate in New York, where stories circulated about why Bubble Yum was so squishy. On playgrounds—where stories are not so easily fact-checked—kids passed along the word that the secret to its chewiness was spider eggs. (In some versions, it’s spider webbing.)

The rumor was embellished to include cautionary tales of kids who woke up with webbing on their faces or spiders crawling out of orifices. One child reportedly bit into a piece and discovered baby spiders. Chilling stories of death abounded; the hysteria eventually grew to include anecdotal reports of cancer. (In fact, stomach acid would almost certainly destroy spiders or their eggs before they could cause any harm to the human body. And in terms of protein, they’re probably more nutritious than gum.)

Not all consumers were agitated. “I chewed it,” said New Jersey resident Michael Reinhart, 12. “I’m not dead yet.”

Sales on the East Coast, which had been brisk, suddenly nosedived. Life Savers needed to take immediate action.

The company first tried to assess the damage. In one telephone survey, some 40 to 50 percent of respondents said they had heard the rumor. Worse, many of them believed it indicated there was a real and serious problem with Bubble Yum.

Another, less formal poll was conducted by Lynn Lehew, a sixth grader in New Jersey. About 30 of the 90 kids in her class believed the spider egg story, she said.

Mortified, Life Savers put private investigators on the case in an attempt to see if the origin of the stories could somehow be traced. Given the fluid nature of playground conversation, this was virtually impossible. The investigation turned up nothing.

Morris believed the best way to combat misinformation was to blanket the public with the facts. Life Savers reached out to parent-teacher associations and school principals in the hopes they could debunk the rumor in classrooms. The company also took out full-page newspaper ads in about 30 major publications, including The New York Times, that addressed the spider egg rumor. It was pointed directly at adults, who would—hopefully—admonish their children about spreading urban legends.

“Someone is telling your kids very bad lies about very good gum,” the ad read.

For Bubble Yum, it was not without risk: While denying the allegation was sensible, it also amplified the idea for millions of newspaper readers. Some publicity firms advised Life Savers to simply ignore the rumors.

But the ad blitz paid off. When another round of phone surveys was conducted, the percentage of people who suspected Bubble Yum of being infested with arachnids had dropped. By summer 1977, sales of Bubble Yum had rebounded, and other soft bubble gums (Bubblicious, Increda-Bubble) entered the market. (In the New York area, however, where the rumor was strongest, sales continued to slump.)

Strangely, the Bubble Yum debacle came at virtually the same time another juvenile treat was experiencing a similar smear campaign. Pop Rocks, the hard candy that fizzed and popped thanks to carbon dioxide, was said to be fatal when mixed with soda. The combination, kids warned, would cause an explosion in the stomach—one that supposedly took the life of John Gilchrist, the actor portraying “Mikey,” a popular character in commercials for Life cereal. (Gilchrist was fine.)

Pop Rocks was not as fortunate as Bubble Yum: The former was more of a fad that quickly fizzled out. It was Bubble Yum that endured, braving the PR crisis to become an evergreen brand. Not that the product was free from controversy. As the insect rumors ebbed, the American Dental Association warned there was another ingredient in Bubble Yum even more insidious than spiders: too much sugar.