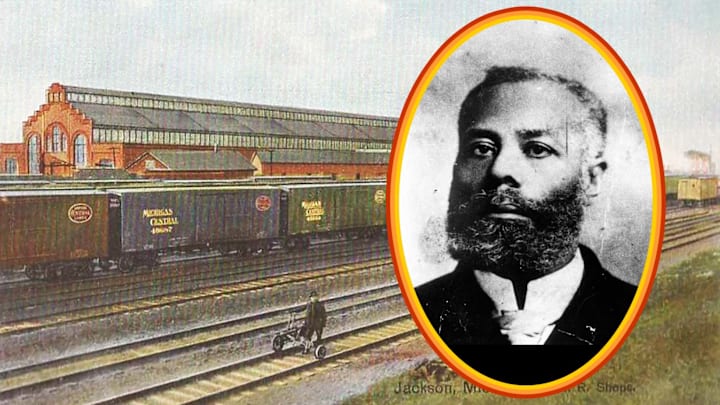

Elijah McCoy’s most famous creation, an automatic oil cup that lubricated steam engines on trains, may have spawned the phrase the real McCoy. He patented over 50 inventions, more than any other Black man held at the turn of the 20th century—and most of them related to railroads. McCoy was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2001 and was the subject of a Google doodle on his birthday in 2022. Here are nine more facts about the prolific inventor.

1. Elijah McCoy’s parents escaped slavery using the Underground Railroad.

McCoy’s parents made their way from Kentucky to Ontario, Canada, where Elijah was born on May 2, 1844. He had 11 brothers and sisters. Elijah spent the earliest days of his childhood on a 160-acre homestead there before the family returned to the States when McCoy was 3. They lived in Detroit and then in Ypsilanti, Michigan, where McCoy’s father, George, opened a tobacco business.

2. He went to Scotland to learn engineering.

Elijah had an obvious aptitude for taking apart and rebuilding machines. His parents saved enough money to send him to the University of Edinburgh to be trained in mechanical engineering, but when he returned to the States shortly after the Civil War, he found slim prospects as a Black engineer. Instead, he got a job as a fireman/oilman on the Michigan Central Railroad, shoveling coal onto fires that powered the steam locomotives’ engines.

3. McCoy’s first patented invention revolutionized trail operation.

Another part of his job involved oiling the axles and bearings on the trains’ wheels as well parts of the engine, a cumbersome process that required trains to stop frequently for service, which delayed shipments, wasted fuel, and wore down the machinery. McCoy was determined to solve this inefficiency. He designed a cup-like apparatus that provided a continuous drip of oil into the locomotive parts while the train was moving, and received U.S. patent number 129,843 in 1872. McCoy’s automatic oil cup was a huge success; as some stories tell it, knock-offs quickly entered the market, and when a company wanted to make sure it bought the original design, it asked for the “real McCoy.”

4. McCoy’s lubricating device proved useful for more than just trains.

Because the automatic oil cup allowed gears and moving parts to be lubricated while in motion, other industries that previously had to stop their equipment for servicing naturally wanted to adopt it. It soon made its way into oil-drilling and mining equipment, factories, naval vessels, construction, and factory tools, among other applications.

Despite the acclaim that the oil cup received, McCoy considered his greatest invention to be a graphite lubricator that he patented in 1915 at the age of 72. McCoy mixed graphite and oil to create a more viscous lubricant that could be used with modern locomotive engines, which ran hotter; the substance allowed engines to move smoothly and reduced the amount of coal and oil needed to operate the trains.

5. McCoy also improved the lawn sprinkler and ironing board.

Most of McCoy’s inventions related to the railroad, but he devised others that most laypeople would recognize. Although he is often credited with inventing the lawn sprinkler, McCoy actually improved upon an existing model. Another Black inventor, Joseph H. Smith, patented a sprinkler design in May of 1897; and an earlier version, by Joseph Lessler, was patented in 1871. McCoy’s design, shaped like a turtle and dispersing the water in a different way, was patented in 1899. McCoy also patented a new portable, foldable ironing board in response to his wife’s complaints about hers.

6. He opened his own company when he was 76.

McCoy worked in Detroit as a railroad consultant to engineering firms beginning in 1882, then opened the Elijah McCoy Manufacturing Company in 1920, making his products himself instead of licensing the designs.

7. McCoy’s second wife was a prominent civic leader and suffragist.

McCoy was married twice, first to Ann Elizabeth Stewart (who died in 1872), and then to Mary Eleanora Delaney in 1873. Elijah McCoy had no surviving children in either marriage.

Mary McCoy made her own mark as a well-known civic leader and suffragist in the Detroit area. She was the only Black member of the Twentieth Century Club of Detroit, a prominent women’s social club, and in 1895 founded the first Black woman’s club with the unwieldy name In As Much Circle of Kings Daughters and Sons. She was instrumental in establishing the Phyllis Wheatley Home for Aged Colored Women in Detroit and the Michigan chapter of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW). She was active in a number of other prominent organizations and suffrage movements as well.

8. Despite his successful inventions, McCoy died impoverished.

Although McCoy’s inventions reportedly generated millions of dollars, McCoy himself netted only a small fraction of that, and lost what he did earn. He assigned the rights to his patents, likely to raise money for other projects and his business, and also likely due to the difficulty a Black inventor would have in selling his product himself.

Elijah and Mary McCoy were injured in a car accident in 1922, and Mary died in 1923; Elijah never fully recovered physically or emotionally. He died on October 10, 1929, at the Eloise Infirmary, a state home for poor residents outside of Detroit. He is buried in Detroit Memorial Park East.

Many of the original buildings at the Eloise complex have been demolished, but as of 2023, a company was running escape rooms, haunted tours, and paranormal investigations at the “Eloise Asylum”—with a portion of the proceeds going to an on-site shelter for unhoused people.

9. Several landmarks in Michigan bear McCoy’s name.

The state of Michigan put a marker in front of McCoy’s former home on Lincoln Street in Detroit in 1974, and Detroit named another street after him in 1975. The first satellite office of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, located in Detroit, is called the Elijah J. McCoy United States Patent and Trademark Office. The city of Detroit also named a neighborhood for McCoy sometime after 2019.

10. “The Real McCoy” phrase may have predated Elijah McCoy’s inventions.

Debate continues about the original source of the phrase the real McCoy. A multitude of theories exist, including the one about McCoy’s lubricating oil cup.

One of the earliest origin stories claims the phrase made it into print as early as 1848, when it appeared in an article in a Scottish newspaper about a con man who tried to pass off an imitation of an expensive hat.

Another source may be a line in an 1856 poem, The Deil’s Hallowe’en (or Devil’s Halloween), that mentions “a drappie o’ the real M’Kay,” often translated as “the real Mackay” and apparently referring to a Scottish whisky by distiller G. Mackay and Co. The poet went by the pseudonym Young Glasgow. In 1883, writer Robert Louis Stevenson apparently used the term the real Mackay in a letter.

The first iteration of real McCoy is usually attributed to a line in an 1881 book by James S. Bond, The Rise and Fall of The Union Club, in which a character proclaims, “It’s the ‘real McCoy,’ as Jim Hicks says.” Other, more unlikely origins include the Hatfield-McCoy feud, rum runner Bill McCoy, and 19th-century boxer Kid McCoy; though those come later than the earlier published mentions.