The Freedom Riders were a brave group of more than 400 civil rights activists, many of whom were just teenagers, who put their lives on the line to dismantle segregated busing in 1961. By doing so, they secured what historian Ray Arsenault called the civil rights movement’s “first unambiguous victory” [PDF]. Here are some essential facts about the Freedom Riders and their mission.

1. The Freedom Riders tested states’ compliance with two Supreme Court rulings.

In the 1946 case Morgan v. Virginia, the U.S. Supreme Court declared segregation on interstate transport was unconstitutional. Another Supreme Court case, 1960’s Boynton v. Virginia, reinforced this decision. By a 7-2 margin, the justices ruled that facilities meant to serve passengers traveling across state lines, like bus station bathrooms and cafés, must be integrated. But both rulings were widely ignored below the Mason-Dixon line, prompting civil rights activists to draw attention to the states’ continuing segregation.

2. CORE’s Journey of Reconciliation in 1947 was a prelude to the Freedom Rides.

When it became clear the Supreme Court’s orders weren’t being followed after the Morgan v. Virginia case, a civil rights organization called the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) sent 16 of its members—eight Black and eight white—on southbound bus rides out of Washington, D.C. Their Journey of Reconciliation began on April 9, 1947, and protested southern states’ illegal segregation. Their itineraries ended in North Carolina, where many participants were arrested.

3. The Freedom Rides of 1961 were based on principles of nonviolence.

James Farmer, Jr., CORE’s co-founder and national director, organized the first Freedom Rides early in 1961. Having been a conscientious objector during World War II, “as a pacifist, I was concerned with finding nonviolent solutions to violent conflict situations domestically,” Farmer told NPR in 1985. Like the riders in 1947, the Freedom Riders of 1961 were Black and white activists who would travel on interstate buses across the South, testing the region’s compliance with the earlier court decisions. But unlike the first group, the Freedom Riders’s destinations were in the deepest parts of the Jim Crow South.

4. Through role-playing, Freedom Riders learned how to prepare for conflict.

CORE prepared riders to turn the other cheek during hostile situations with “intense role-playing sessions.” Activists would berate trainees at simulated lunch counters or bus terminals to see how they’d react and then offer feedback. According to Farmer, some of this role-playing became “all too realistic.” The sessions proved effective, and other civil rights organizations adopted similar training methods.

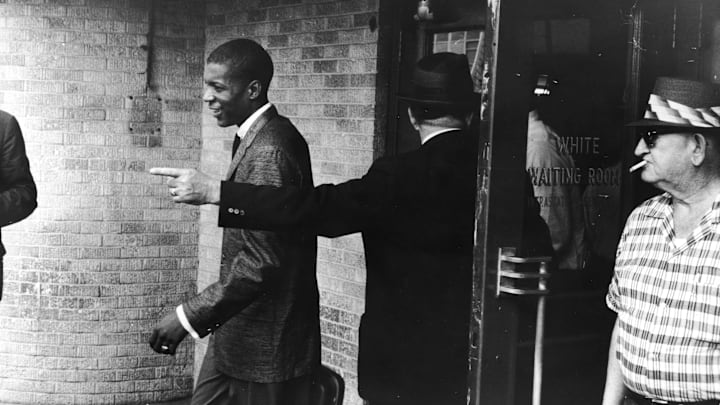

5. Future Congressman John Lewis was one of the original Freedom Riders in 1961.

Already a veteran of sit-ins, John Lewis was one of the first 13 activists CORE enlisted for their bus-riding campaigns in 1961. The crew was divided into two groups: one rode a Greyhound bus and the other took a Trailways bus. Both left D.C. on May 4, 1961, headed for New Orleans. Five days into the trip, Lewis and other riders were attacked by Ku Klux Klan members at a whites-only waiting room in the Rock Hill, South Carolina, Greyhound terminal. “They left us lying in a pool of blood,” Lewis told the Washington Post.

In 2009, former Klan supporter Elwin Wilson admitted he was the man who had beaten Lewis, and apologized in person to the Congressman. Lewis forgave him.

6. Martin Luther King, Jr. warned the Freedom Riders of dangers ahead.

Following the violence at Rock Hill, both bus groups proceeded to Atlanta. There they had dinner with Martin Luther King, Jr. He was asked to become a Freedom Rider himself, but declined because he was on parole. (According to Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee co-founder and former NAACP chairman Julian Bond, his refusal caused a rift between older and younger civil rights activists.) Before the evening ended, King told a Jet reporter who was traveling with the riders, “You will never make it through Alabama.” Unfortunately, his words were prophetic.

7. In Alabama, the Klan beat the Freedom Riders with impunity.

A violent mob attacked the Greyhound group in Anniston, Alabama, on May 14, setting fire to the bus and savagely beating its passengers. The same day, another Klan-led crowd descended on the Trailways riders in Birmingham, Alabama. Eugene “Bull” Connor—a devout segregationist and the city’s public safety commissioner—struck a deal with Klan leader Bobby Shelton to intentionally keep the police away from the Trailways station for 15 minutes after the bus arrived. The Klan and its allies attacked the Freedom Riders without fear of arrest.

8. The Freedom Riders completed their journey by plane.

Lewis and the rest of the original 13 Freedom Riders made it to New Orleans, but not by bus. Because of the escalating violence, Farmer halted the campaign and directed the activists to fly to their destination. By then, national news outlets had run reports and footage of the attacks on the peaceful protestors, and public opinion was turning toward them. More Freedom Riders stepped up to continue the campaign.

“We recognized that if the Freedom Ride was ended right then after all that violence, southern white racists would think they could stop a project by inflicting enough violence on it,” activist Diane Nash told History.com. Nash, then a student at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, helped lead a second wave of Freedom Riders, eventually numbering in the hundreds.

9. More than 300 Freedom Riders were arrested.

Before the year was out, more than 60 Freedom Rides had been organized. Participants were routinely arrested, with many landing in the Mississippi State Penitentiary, a.k.a. Parchman Farm. (Lewis was held there for 37 days.) Governor Ross Barnett instructed guards working at the facility to “break their spirits, not their bones.” In keeping with that decree, they threatened the activists by taking away necessities like mattresses and toothbrushes, but the activists used their detention to strengthen their organization and resolve.

10. The Kennedy administration finally answered the Freedom Riders’ pleas.

The federal government was slow to respond to the Freedom Riders’ campaign and the ensuing racist violence. But when Soviet newspapers started reporting on movement, Kennedy sensed that the attacks were reflecting badly on the United States’s standing in the world. Partly for this reason, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy asked the Interstate Commerce Commission to take action. “The time has come for this commission to declare unequivocally by regulation that a Negro passenger is free to travel the length and breadth of this country in the same manner as any other passenger,” he wrote.

On September 22, 1961, the ICC ordered the full integration of all interstate buses and their terminals. That November, buses were required to post signs saying, “Seating aboard this vehicle is without regard to race, color, creed, or national origin, by order of the Interstate Commerce Commission.”

11. The Freedom Riders’ example inspired successful civil rights campaigns.

By striking a blow against segregation, the Freedom Riders demonstrated the effectiveness of nonviolent civil disobedience. From then on, nonviolence became the primary tactic for the movement in its push for voting rights, labor rights, and other causes. Moreover, they brought national and international attention to the larger struggle for civil rights, attracting new activists and organizers to the movement. And, in addition to the ICC's order, their example helped bring about landmark legislation for equality, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

A version of this story originally ran in 2021; it has been updated for 2024.