The post-White House lives of presidents have been intensely scrutinized, but what becomes of former vice presidents? Four have assumed the presidency after the sitting president’s death by natural causes: John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, Calvin Coolidge, and Harry Truman. Four became POTUS after presidents were assassinated: Andrew Johnson, Chester Arthur, Theodore Roosevelt, and Lyndon Johnson. And one, Gerald Ford, became president after his boss resigned [PDF].

Only four sitting veeps have actually been elected president: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Martin van Buren, and George H. W. Bush. That leaves a lot of former vice presidents who need to find gainful employment following their terms. Here’s what happened to a few notable ones.

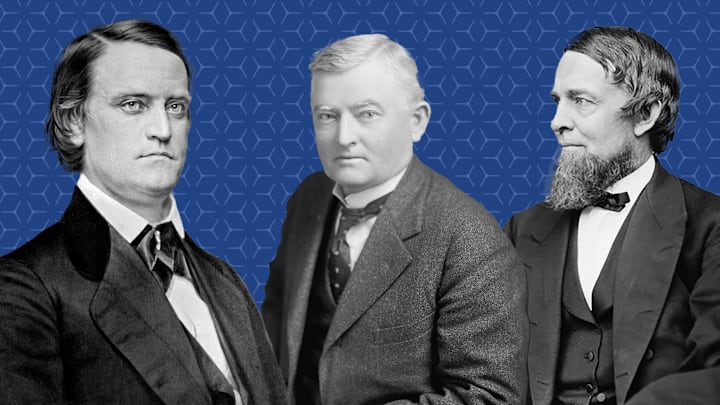

- John C. Breckenridge

- Dan Quayle

- John Nance Garner

- Henry Wallace

- Thomas A. Hendricks

- Schuyler Colfax

- Aaron Burr

- Hubert H. Humphrey

John C. Breckenridge

Breckenridge, who served under James Buchanan from 1857 to 1861, didn’t rest on his laurels after his stint as VP. Instead, the Kentuckian became a United States senator on the same day he left office. This arrangement didn’t last long, though; in December of that year the Senate expelled Breckenridge for supporting the Confederacy. He then joined the Confederate States Army, where he rose to the rank of major general and fought in several major conflicts, including the Battle of Shiloh. In 1865 he became the Confederacy’s secretary of war. After the Civil War, Breckenridge returned home to Kentucky and resumed work as a lawyer.

Dan Quayle

After his stint as George H.W. Bush’s second in command, Quayle returned to the private sector as an investment banker. He’s the chairman of Cerberus Global Investments LLC, a large private equity firm, and also spent a couple of years as a professor at the Thunderbird School of Global Management. Quayle also made his mark as a writer by penning three books, including Standing Firm: A Vice Presidential Memoir, which spent 15 weeks on The New York Times bestseller list.

John Nance Garner

Many vice presidents are probably appreciative that their running mate helped bring them to Washington. John Nance Garner wasn’t one of them, though. Although he served as Franklin Roosevelt’s vice president during FDR’s first two terms, Garner didn’t always agree with the New Deal’s policies. Some Democratic Party leaders agreed with Garner and convinced him to run for the presidency in 1940. Garner might have had a chance at winning the Democratic nomination if his boss hadn’t decided to run for a third term. Garner, undeterred, decided to gun for FDR’s job anyway. Roosevelt hammered Garner in the primaries and thumped him 946–61 in the balloting for the nomination at the Democratic Convention. Although Garner obviously couldn’t return to his VP post, he maintained his role in the party by offering advice to sitting Democratic leaders until his death in 1967 when he was nearly 99 years old.

Henry Wallace

Garner’s successor as Roosevelt’s VP had an interesting post-Washington career, too. Wallace, who had previously served as secretary of agriculture under Roosevelt, returned to his farm in South Salem, New York, and started trying to develop new breakthroughs in agriculture science. In addition to pioneering hybrid corn, he also co-authored a history of the food, Corn and Its Early Fathers. Wallace was most focused, though, on creating the “perfect chicken.” He may have succeeded; as late as 1990 nearly half of the eggs consumed worldwide were from Wallace's breed.

Thomas A. Hendricks

Grover Cleveland’s running mate in the 1884 served a fairly short term. He took office on March 4, 1885, and then fell ill in November of the same year. Hendricks quickly passed away, but he lives on in the hearts of coin collectors everywhere. He’s the only vice president who didn’t later serve as president to have his likeness on American paper money. His face adorned the 1886 $10 silver certificate.

Schuyler Colfax

Colfax, who had formerly been speaker of the House, served as vice president during Ulysses S. Grant’s first term in office, but his stint as VP didn’t end so well. Colfax got caught up in the Credit Mobilier scandal, a convoluted bit of graft that involved congressmen granting subsidies to railroads in exchange for the right to buy cheap shares of stock. Colfax may have left office in shame, but he bounced back nicely and spent his last years as a traveling lecturer. Unfortunately, this lecturing also proved fatal to him: Colfax had to walk just under a mile in -30°F weather in 1885 to make a train connection for a lecture. Colfax made it to the depot, but the strain brought on a fatal heart attack.

Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr’s vice presidency was perhaps the most unusual example in American history. Burr ran with Thomas Jefferson in 1800, and in doing so helped accentuate one of the flaws in the Constitution.

According to the original Constitution, members of the Electoral College cast two votes, and whoever got the second-most votes became vice president. Jefferson and Burr’s Democratic-Republican Party had figured out the best way to vote to put the two candidates in their respective offices. Something got seriously screwed up, though, and Jefferson and Burr ended up tied with 73 votes apiece. Although Congress eventually voted Jefferson into the presidency, Jefferson didn’t quite trust Burr any longer, and he never really regained his footing within the administration.

After Jefferson declined to put Burr on his ticket in 1804, Burr ran unsuccessfully for governor in New York. Burr felt his old rival Alexander Hamilton was responsible for this loss, and while still serving as vice president, killed Hamilton in a duel in New Jersey.

Shooting a Founding Father in a duel would have ended the careers of many politicians, but Burr decided to up the ante. Along with General James Wilkinson, he hatched an absurdly ambitious plan to launch a military attack on Mexico, where he hoped to establish an independent country. Unfortunately, Wilkinson realized this plan was doomed and tipped off President Jefferson about what Burr was up to. Although Burr beat a treason rap for plotting the war (partially thanks to the fleet-footed legal work of his lawyer, Henry Clay), he became a much-vilified character in the U.S. He fled to Europe for four years, where he supposedly tried to talk Napoleon into invading Florida with him, and died in 1836.

Hubert H. Humphrey

Lyndon B. Johnson’s vice president made an unsuccessful bid for the presidency in 1968, at which point he returned home to Minnesota to serve as a professor. Humphrey held a more unusual job after leaving Washington, though; he was also chairman of the Encyclopaedia Britannica’s board of consultants. Humphrey eventually got back into the political game, though, and in 1971 went back to the Senate for seven more years until his death.

Read More About Presidents:

A version of this story was published in 2009; it has been updated for 2024.