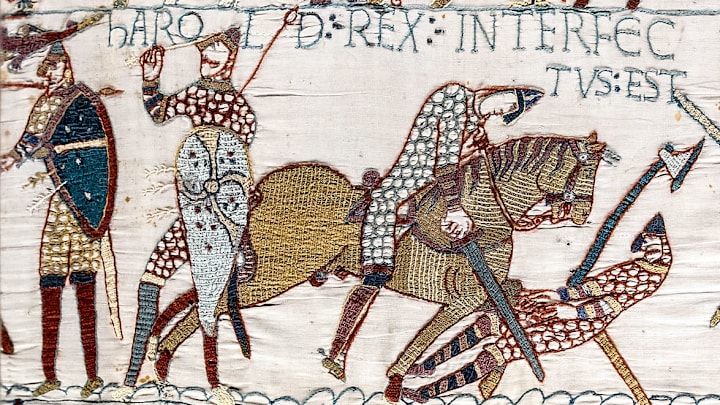

The Bayeux Tapestry is one of the most famous pieces of art in the world. The 950-year-old, 230-foot chronicle of the Norman Conquest and the Battle of Hastings was embroidered in the years following William the Conqueror’s invasion of England in 1066. It’s both an invaluable historical document and an impressively long-lasting textile.

Historians have been analyzing and discovering elements of its story for centuries. The idea that King Harold of England was killed by an arrow to the eye originated in the tapestry. A bright star that appeared in the sky a few months after Harold’s coronation—which many saw as a bad omen and portent of doom—also shows up in the tapestry; centuries later, astronomers realized it was Halley’s comet. (Edmund Halley himself wasn’t born until 1656.)

The Bayeux Tapestry also features a frequent motif: penises.

There are a lot more of them in this medieval work, created to decorate a church, than anyone might reasonably expect. And the exact number of them has proven to be a hot topic for debate.

“Anatomically Fulsome”

George Garnett, a professor of medieval history at St. Hugh’s College, University of Oxford, announced in 2018 that he had tallied up the willies and had a total of 93: Five belonging to people and a fairly staggering 88 to horses.

You May Also Like:

- Why Do Babies in Medieval Paintings Look So Scary?

- This Medieval Manuscript Has Stumped Codebreakers for More Than a Century

- Why Medieval Artists Doodled Killer Bunnies in Their Manuscript Margins

Add Mental Floss as a preferred news source!

But there might be one more—and that is the source of the controversy. A 94th penis may be hanging out of the bottom of a man’s tunic, according to Dr. Christopher Monk, a heritage consultant who goes by The Medieval Monk. “I am in no doubt that the appendage is a depiction of male genitalia—the missed penis, shall we say. The detail is surprisingly anatomically fulsome,” he told the HistoryExtra podcast.

The figure in question is holding two clubs and running along the lower border of the tapestry with, possibly, his junk in plain sight. Garnett, countering Monk’s argument, insists it is a scabbard for a sword. It certainly appears ambiguous to the naked eye. If anything, it looks more like a holster for a pistol, and the end of it also seems to have something of a glow, like E.T.’s finger or Rudolph’s nose, which academia has yet to address.

Coded History

If it is a penis, what does it mean? The nuns who likely created the Bayeux Tapestry put in a huge amount of work, and the bishop who commissioned the piece, the half-brother of William the Conqueror, intended it to be a monumental record of William’s triumph. And male genitals are depicted in art to show power and virility. The largest one on show hangs from William the Conqueror’s horse, and the second-largest appears on the steed of King Harold, perhaps as a show of respect to the late ruler.

“Medieval people were not crude, unsophisticated, dim-witted individuals. Quite the opposite,” Garnett said on the podcast. The tapestry’s designers and artisans were obviously educated and seem to be subverting the heroic story of the conquest with visual symbols and allusions, he said: “This is a serious, learned attempt to comment on the conquest, albeit in code.”

The meaning of the specific soldier with the maybe-member is harder to pin down. He could be a symbol representing fearlessness or bravery, or the object might be a scabbard, or it could be a simple mistake in the embroidery.