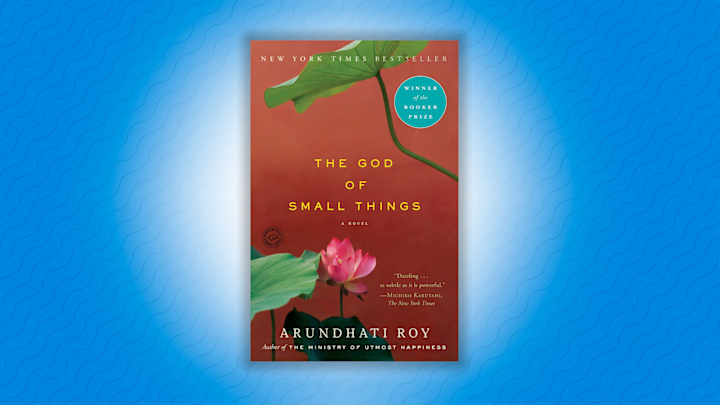

The story of Estha and Rahel, fraternal siblings who struggle with the cultural influences of their native India, is at the heart of The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy’s groundbreaking 1997 novel. As children, the two attempt to process the struggles of their mother, Ammu, and their extended family, with the book’s perspective filtered through their young eyes. Roy then revisits the two as adults, who reunite and attempt to sift through their shared grief. Here’s what you need to know about Roy’s unforgettable bestseller.

- The God of Small Things was Arundhati Roy’s first novel.

- The God of Small Things began with a single image.

- Roy’s training as an architect influenced her writing.

- Roy drew upon her real life for many of the book’s details.

- The title was a last-minute decision.

- The God of Small Things earned Roy a massive advance.

- It was an instant success, both critically and commercially.

- Roy was charged with obscenity because of the book.

- There was a TV show based on the novel.

- It took Roy 20 years to publish her next work of fiction.

The God of Small Things was Arundhati Roy’s first novel.

Roy didn’t set out to be a novelist—she originally went to school for architecture, which she described as “a practical necessity” because “I needed to have a profession, I needed to earn my own living just to be able to escape what society would normally have had in store for me.” But she soon left the field to pursue work in India’s film industry, writing the screenplay for the movie In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones (1988), which won an Indian National Film Festival award for Best Screenplay. She then began working on the manuscript for what would become The God of Small Things in 1992, completing it five years later.

The God of Small Things began with a single image.

It took Roy more than four years to write The God of Small Things, and as she told Salon in 1997, “I wrote it out of sequence. I didn’t start with the first chapter or end with the last chapter. I actually started writing with a single image in my head: the sky blue Plymouth with two twins inside it, a Marxist procession surrounding it. And it just developed from there.” She noted that “If someone told me this was how I was going to write a novel before I started writing it, I wouldn’t believe them.”

Roy’s training as an architect influenced her writing.

“In buildings, there are design motifs that occur again and again, that repeat—patterns, curves,” she told Salon. “These motifs help us feel comfortable in a physical space. And the same works in writing, I’ve found.”

Because writing is “about design” for the author, even “the way words, punctuation and paragraphs fall on the page is important … the graphic design of the language. That was why the words and thoughts of Estha and Rahel, the twins, were so playful on the page ... I was being creative with their design. Words were broken apart, and then sometimes fused together. ‘Later’ became ‘Lay. Ter.’ ‘An owl’ became ‘A Nowl.’ ‘Sour metal smell’ became ‘sourmetal smell.’ ”

Roy drew upon her real life for many of the book’s details.

Though The God of Small Things is a work of fiction, Roy took inspiration from her own life when crafting the story. In the book, much of the action takes place in Ayemenem, India, the village where she grew up and saw the archaic caste system firsthand. Her grandmother also ran a pickle factory like the one owned by Rahel and Estha’s family.

This is where readers are introduced to Velutha, one of the workers at the factory and a member of India’s “untouchable” caste, who begins an ill-fated affair with Ammu, Rahel and Estha’s mother. Like Ammu, Roy’s mother was a divorcee who had to deal with the stigma of a failed marriage.

Even the family’s trips to see The Sound of Music have some basis in reality—in an interview, Roy recalled her family taking two-hour car rides to the city of Cochin to see the movie around seven times when she was a kid. If you read the book, you’ll know that she wasn’t exactly a fan of Julie Andrews’s big-screen classic.

The title was a last-minute decision.

In an interview on the HarperCollins website, Roy revealed that the book’s evocative title wasn’t there from the start. In fact, there was no title until late in the process.

“This novel didn’t have a title until the very last minute,” Roy said. “I didn’t know what to call it, there were lots of ideas and suggestions but I just remember printing out the manuscript and just printing out the title at the last minute.”

Though the decision on a title came down to the wire, the themes in Roy’s writing made many people believe it was the plan all along.

“One of the chapters was called The God of Small Things, I don’t know how that happened,” she said. “When I read the book now I can’t believe the amount of references there are to small things, but it was absolutely not the case that I started with the title and built the novel around it.”

The God of Small Things earned Roy a massive advance.

Roy was paid a combined $1.6 million advance from various publishers around the world for The God of Small Things, a record for an Indian author at the time. But if she felt pressure to live up to her massive advance, she didn’t show it: In an interview with London’s The Independent, the author said, “It’s their business risk ... I trust my book.”

It was an instant success, both critically and commercially.

The hefty advance certainly paid off for the book’s various global publishers: In its first six months, The God of Small Things sold 350,000 copies internationally, becoming a bestseller in the U.S., the UK, and in Roy’s home country of India. The book also took home the prestigious Booker Prize. The novel has since gone on to sell more than 6 million copies worldwide.

Roy was charged with obscenity because of the book.

The God of Small Things tackles social and political in India, including the caste system, the treatment of women, and the country’s views of the British. And while the book won support from critics and readers worldwide, the reception at home was far more complex, especially among politicians on both the left and right. For one lawyer in particular, the depiction of sex between a Syrian Christian woman and a member of a lower class at the end of the book was grounds to file obscenity charges against Roy.

The attorney, Sabu Thomas, brought the charges against her in Kerala, India, the same region where both the book takes place and Roy grew up. “When the charges were first made, I was very upset,” Roy told Salon in 1997. “Now, I realize that this is what literature is about. This is the fallout of literature.”

The ordeal dragged on for 10 years, with Roy being summoned to multiple court appearances; failing to show up even once could have led to her arrest. In the end, a new judge took over the case and dismissed it. More recently, Roy has found herself under threat of prosecution in India for remarks she made about Kashmir in 2010.

There was a TV show based on the novel.

In 2007, Roy told The Progressive Magazine of The God of Small Things, “I wrote a stubbornly visual but unfilmable book.” (She apparently even told her agent to make Hollywood studios beg for the rights—and then refuse them.) That said, a TV show based on the book (with the characters’ names changed) did air on Pakistani TV in 2013. The novel also inspired a song.

It took Roy 20 years to publish her next work of fiction.

Fans hoping Roy would be quick with a follow-up to The God of Small Things had to learn to be patient—at least in terms of her fiction work. After the book was published, she doubled down on her non-fiction writing, releasing political essays and interview collections.

Her second novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, was published in 2017. The book explores India’s culture through the lens of Anjum, a transgender woman, and Tilo, an architect on the cusp of activism. Roy spent 10 years writing the book, and once it was finally published, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness was met with critical acclaim—it even found its way onto the longlist for the Man Booker Prize in 2017. As if history was repeating itself, the novel was followed up by her 2019 collection My Seditious Heart: Collected Non-Fiction.

Discover More Facts About Famous Novels:

A version of this story ran in 2022; it has been updated for 2024.